Benefiting a Multitude

The world of the Soupe Populaire, Casablanca

Conditions for the 40,000 Jews in Casablanca’s mellah (Jewish quarter) during and after World War II were shocking. The vast majority of the mellah‘s children suffered from malnutrition, lack of clothing, and very limited education. Elias Suraqui noticed this and wanted to make an impact. Born in Oran, Algeria in 1893, he had come to Morocco as a soldier during World War I. There he studied architecture and, together with his brother Joseph, built modern buildings for the French protectorate. In 1941 the secular, very Jewishly identified Suraqui decided he must find a way to aid the unfortunate: he gathered donations and founded the Soupe Populaire Soup Kitchen for children. Its aim was to provide hot meals as well as to educate underprivileged young Jewish children.

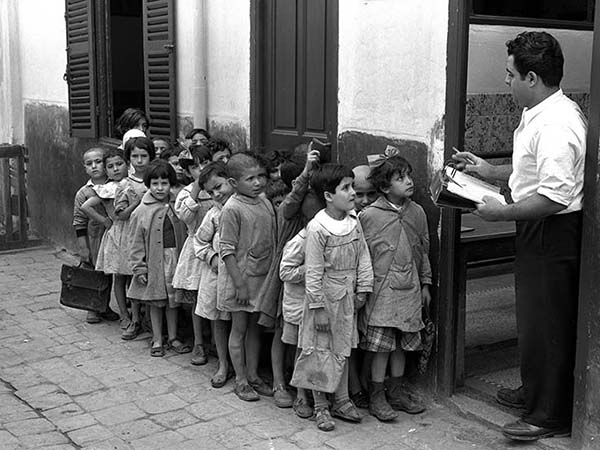

In 1948, JDC increased its activities in the Muslim world, and Suraqui’s was one of many locally run organizations to benefit. JDC strategically decided to prioritize childcare at the possible expense of other goals. From 1948-1964 under JDC sponsorship, Suraqui’s Soupe Populaire fed and cared for 300 6–8-year-olds each year.

The JDC fully financed the Soupe Populaire’s food costs, coordinated with the Alliance Israelite Universelle to provide teaching staff, and with Oeuvre des Secours aux Enfants (OSE ) to provide medical care. In addition to monetary, educational, and medical aid, JDC provided nutritional expertise and training to the Soupe Populaire. On the macro level, JDC staff intervened politically with the government on behalf of the Jewish community, obtaining funding for schools and summer camps, as well as making aliya possible.

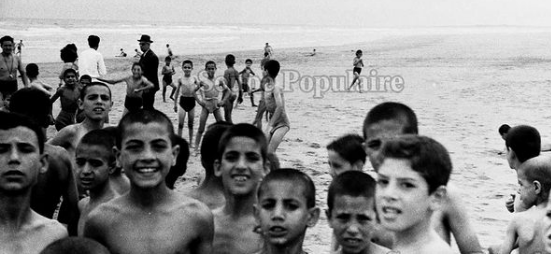

In photos from the 1940s and 1950s, the majority of children are in rags with shaved heads and swollen eyes, while photographs from the 1960s show children well dressed and in good health. Thus, the results of JDC’s policy were dramatically visible: a drastic reduction in contagious diseases, and stronger, more active children.

Ultimately, Suraqui emigrated to France in 1961 and received the Legion of Honor for his charitable work in Morocco. Eventually, his son Daniel decided it was time that his father’s many impressive documents and photographs saw the light of day. He needed to tell the story of the Casablanca Soup Kitchen for Children, and decided to create Wikipedia entries in Hebrew, English and French. Daniel turned to the JDC Archives website, typed Soupe Populaire and Suraqui into the search page, and discovered hundreds of citations regarding his father’s work. Seeing the scope of the work strengthened his drive to publicize what he now sees as his father’s holy work, which benefitted thousands of poor children.

Daniel appreciates that the documents about the Soupe Populaire on the JDC Archives website are not limited to figures and statistics, but rather add a human element. For example, this excerpt from an annual report provides a more personal overview of the children’s experiences at the Soupe Populaire:

Daniel writes:

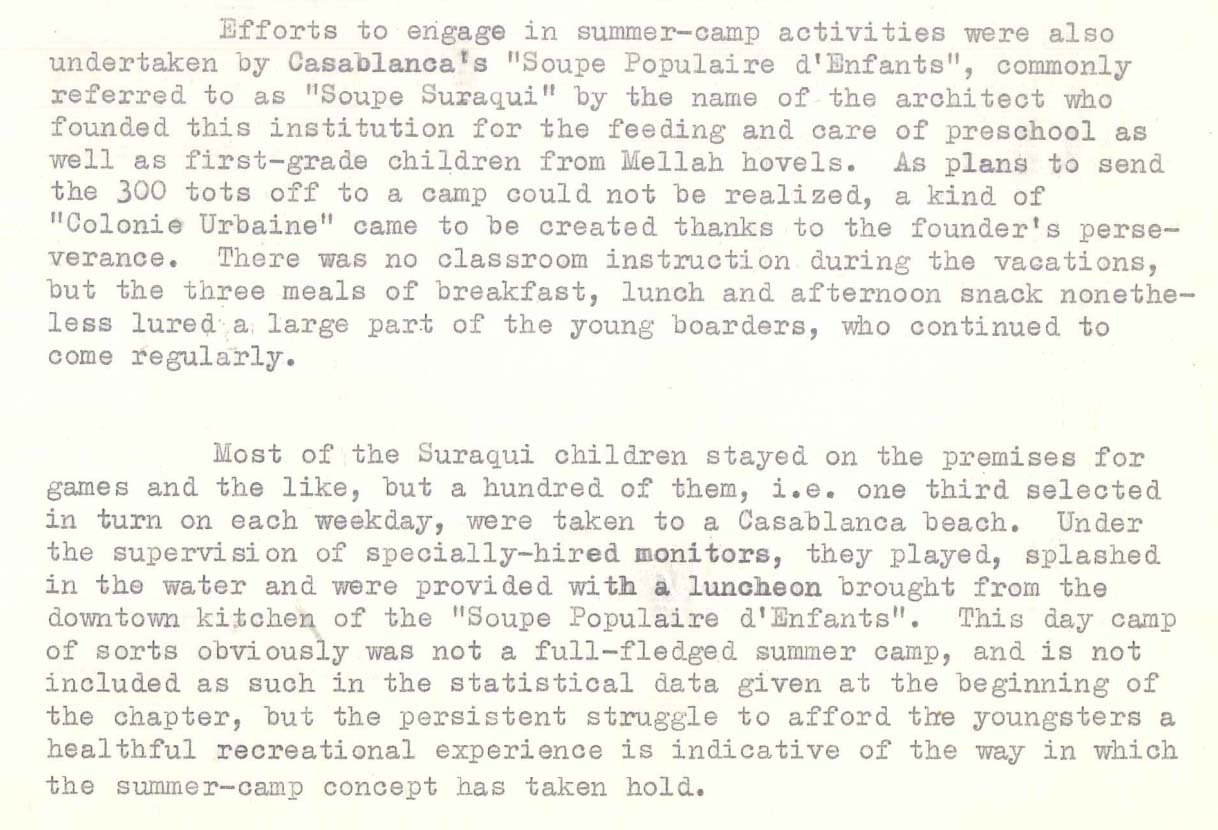

There is an emotional aspect to this quote that pierces through the technical talk. Summer camps are a bubble of oxygen, of discovery, of extraordinary liberation for children who are deprived of the essentials. For all . . . who took it upon themselves to improve the condition of childhood, feelings are mixed. On the one hand, the satisfaction of giving 5,000 children an extraordinary opportunity to get some fresh air, on the other hand the frustration of leaving 30,000 other children with similar needs on the sidelines. Why some and not others? In this context, the ‘Urban Colony’ demonstrates inventiveness, spending is minimal . . . the only charge is a bus to transport the children that the community makes available to the Soupe Populaire. The result can be seen in the photos of the children on the beach who are exploding with joy. As Mr. Kirsch mentions in his report, the ‘Urban Colony is not a summer camp’ but it is the expression of a human will to correct natural injustice.

Growing up, Daniel spent time at the soup kitchen, guiltily eating more than his share of “the most amazing chocolate” provided by JDC, but only through his research did he fully appreciate the joint work undertaken by his father and JDC. With locals running day-to-day operations and JDC providing their end of the bargain, the result saved thousands of Moroccan Jewish children and provided them with a better future.

This story was shared with the permission of Daniel Suraqui, author of Wikipedia articles published in French, English, and Hebrew, as well as an Instagram account devoted to the Soupe Populaire. He writes: “Other similar local institutions, such as Em Habanim founded in 1942 by Moïse and David Bendayan, and the Orphanage Murdoch Bengio founded in 1953 by Celia Bengio, can find their own histories also told in the JDC Archives. They contain the stories of a few people whose action benefited a multitude.”