More Than Just an ID Card

JDC’s mission as told through employee identification documents

By Abra Cohen and Vivian Wolkowicz

Historically, JDC staff have been present on the ground in war-torn regions to assist vulnerable populations. Amid this atmosphere, papers attesting to their identities and professional affiliations were their protective talismans, allowing them to maneuver between combative countries, changing laws, and regimes. Crossing borders and checkpoints in pursuit of JDC operations, these passes of neutrality ensured that the work of JDC could continue in challenging times.

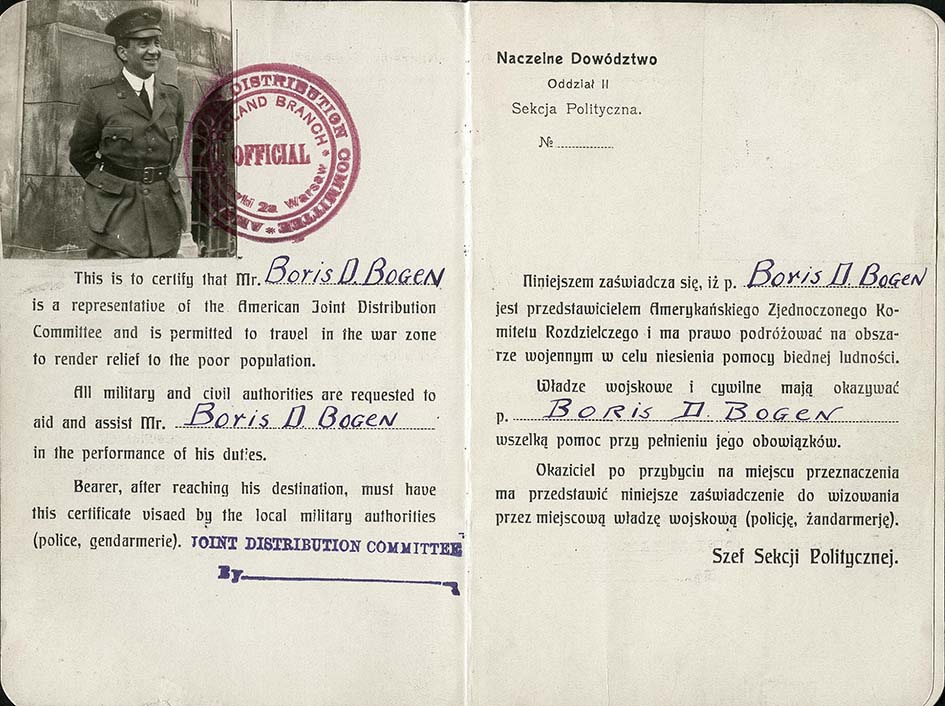

For instance, following World War I, peace brought new crises throughout Europe and Russia as hundreds of thousands of Jews fell victim to disease, famine, pogroms, displacement, and new hostilities in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s collapse. As a representative of JDC, Boris Bogen was sent to Poland in 1920 to assess and assist, with an identification document stating:

“This is to certify that Mr. Boris D. Bogen is a representative of the American Joint Distribution Committee and is permitted to travel in the war zone to render relief to the poor population. All military and civil authorities are requested to aid and assist Mr. Boris D. Bogen in the performance of his duties. Bearer, after reaching his destination must have this certificate visaed by the local military authorities (police, gendarmerie).”

Written in Polish and English, the ID features a photograph of Bogen dressed in uniform in the upper left-hand corner. The stamp, issued by JDC’s Poland branch in Warsaw, imbues the document with a level of authority for the region, attesting to his official position. With the Russo-Polish war and the constant threat of pogroms which impelled JDC to continue the relief effort it had initiated during World War I, this simple document afforded Bogen access to serve Jews in the direst of circumstances. Surveying the situation, his reporting enabled further assistance to follow with urgently needed sanitary, medical, and childcare programs initiated throughout the region.

However, papers were not always enough protection. Sadly, during the same mission, Bogen’s colleagues Israel Friedlaender, JDC Commissioner to the Ukraine, and Rabbi Bernard Cantor, a volunteer in JDC’s unit Number 1 in Poland, were mistaken for Polish officers and killed by Bolshevik soldiers in July 1920.

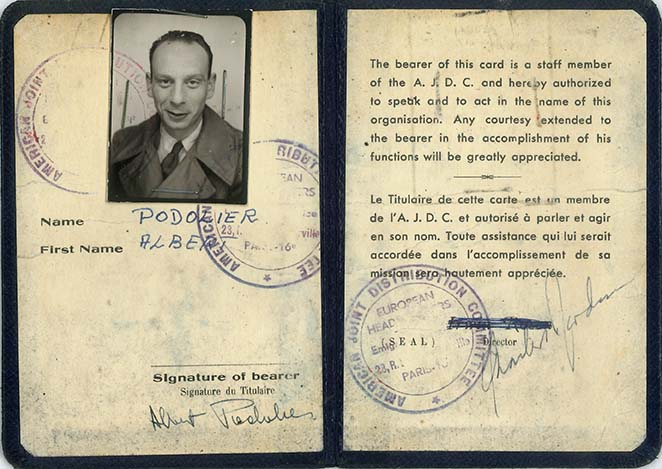

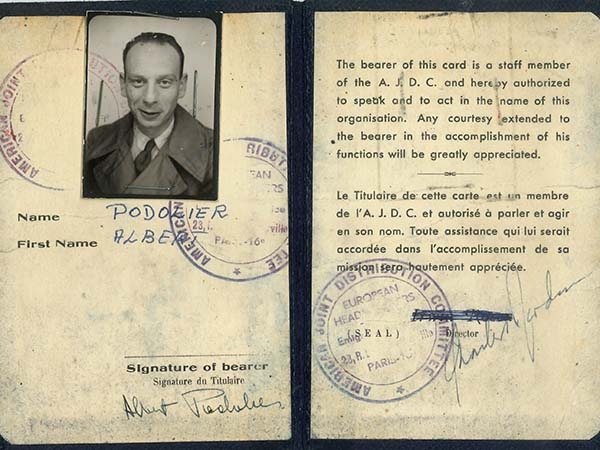

Carrying a JDC identification document was also important while working for the organization in the shambles of postwar Europe. Albert Podolier, a Romanian native who found himself navigating the tumultuous landscape of Europe in the immediate aftermath of World War II, had such a document in the form of a French work permit.

Podolier’s journey led him from Vienna to Paris, where his path intertwined with the mission of JDC, dedicated to aiding refugees displaced by the war. The work permit, showing signs of wear and tear, written in English and French and bearing the stamp of JDC and the signature of then Director of Emigration Charles Jordan, grants Podolier, a survivor, authority to act on behalf of the organization.

The work permit, together with other documents in Podolier’s file, provides a narrative highlighting the progression of his career. Although the details are more limited than with Boris Bogen, valuable insights can be gained from the events described in the documents.

In 1946, Podolier began his service with JDC as a clerk. His duties were varied and often involved waiting for trains to escort survivors seeking safety. These refugees were traveling from Eastern Europe to Western Europe in search of rebuilding their lives. The nature of his work was critical and grueling. Long hours in the cold waiting for trains tested his resilience.

Podolier faced a setback that challenged his fortitude. Just three weeks after receiving a new American Army Air Force leather jacket from the JDC, it was stolen, exposing him to the harsh winter cold. Podolier, who relied on JDC for his clothing, could not afford a replacement and reached out to the “Union of Clerical and Other Employees of the Paris Region.” He eventually received advanced funds from JDC to purchase a new overcoat.

Podolier was promoted to a documentation role and later became a liaison representative within the Emigration Department, providing assistance to Jewish survivors seeking to emigrate from postwar Europe via France. This role placed him at the crossroads of international communication, with a variety of responsibilities including serving as a bridge between the department and several foreign consulates. Podolier’s duties were so varied that he even “arrange[d] for rapid marriages for DPs.”

The nature of Podolier’s work as a liaison representative suggests a significant development in his skillset. Effective communication, cross-cultural understanding, and a deep knowledge of emigration processes—including documentation requirements, consular rulings, and French regulations—were essential for success in this role.

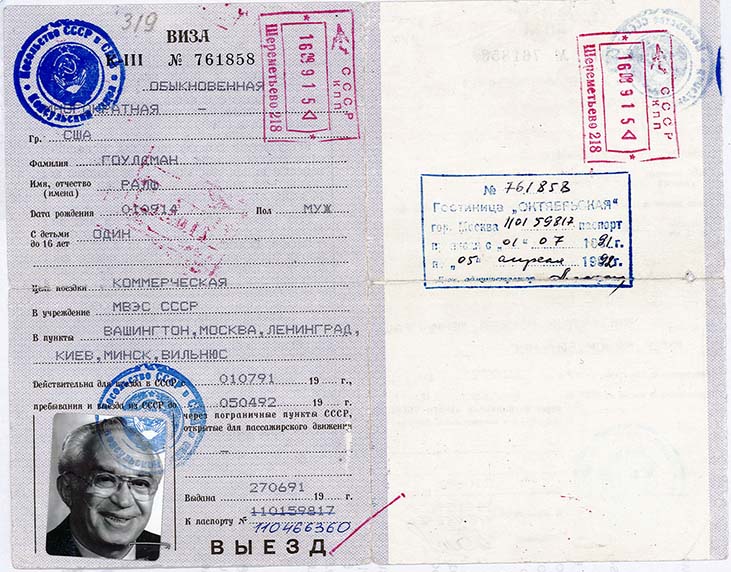

Representing a third important period in JDC’s history, the final identification is connected to JDC’s re-entry in the Soviet Union in 1988 with the mission of reconnecting Soviet Jews to their heritage. JDC’s Honorary Executive Vice President, Ralph Goldman, who spearheaded JDC’s return to the Soviet Union, was issued a visa allowing travel between Washington, Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Minsk, and Vilnius, for the period between July 1, 1991, and April 5, 1992. This was the first time since 1938 that anyone from JDC was issued a multi-entry visa that allowed travel throughout this region.

The typewritten travel document composed entirely in Russian might have seemed surreal for its owner after such a long period of absence from the country. With multiple stamps, the visa shows signs of mileage as well as meticulous record keeping, its worn folds indicating repeated opening and closing.

This visa reflects the outcome of Goldman’s extended and sensitive negotiations with Soviet officials in the Department of Religious Affairs, successfully navigating JDC’s return to what became the former Soviet Union. JDC’s subsequent efforts to rebuild local Jewish communities, including the training of educators, religious leaders, and communal professionals, the building of Judaic libraries and the creation of the Hesed program to support elderly Jews would provide a foundation for the future transformation of Jewish life there. And to think, these efforts wouldn’t have been possible without this foldable piece of delicate paper, so easy to lose, yet now equally important to treasure.

The Bogen, Podolier, and Goldman identification documents provide insight into the challenges and opportunities faced by the organization and its representatives in both Western and Eastern Europe during three watershed moments in 20th-century Jewish history.