A JDC Archives Fellow Discusses Her Research on Jewish Life in 1950s Poland

Interview with Frankee Lyons

Frankee Lyons was the 2020-2021 Nathan & Sarah Chesin/JDC Archives Fellow. Her research in the JDC Archives focused on the Joint’s operations in Poland during the time of migration and political change from 1957 through the mid-1960s preceding the March 1968 antisemitic campaign. She is a PhD candidate in Modern Eastern European History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. During the 2019-20 academic year, she was a visiting researcher in Warsaw, Poland at the Institute of Political Studies at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Q: Can you tell us how you came to this research project on Jewish life in Poland in the 1950s?

A: While working on my bachelor’s degree at the George Washington University, I studied for a semester at the Warsaw School of Economics. I spent that time working on my honors thesis about the legacy of Claude Lanzmann’s landmark documentary Shoah in Poland and taking classes on Polish Jewish history and the Holocaust.

I embarked on that program believing that the Polish Jewish story in many ways ended in 1945, but during my studies I encountered stories of Jews who lived in Poland during the communist period. These stories challenged my preconceptions and inspired me. I became more interested in the early post-Stalinist period in Poland, particularly the nature and tribulations of the Jewish community during that time. I realized how little scholarship exists on 1950s Polish Jewish history, especially in English and centering around the effects of the political changes of 1956 and the Polish Thaw.

Q: Your virtual lecture at the JDC Archives focused on JDC operations in Poland from 1957 to the early 1960s. What is it about that period that drew you in?

A: This period, beginning in 1956, was a time of political change and possibility in Poland. After Josef Stalin’s death in 1953, Poland and other Eastern Bloc countries experienced destalinization and the end of Stalinist-era repression. Poland soon experienced the Polish Thaw, which saw greater socio-political liberalization. Amid these changes, Polish Jews emigrated by the tens of thousands, and tens of thousands of Jews repatriated from the Soviet Union to Poland. The JDC, which had been expelled from Poland by the Stalinist regime in 1949, was invited to return to the country in 1957 to assist Jewish repatriates.

I was drawn to this story because of its unexpected dynamism. Many people are surprised to hear that there were any Jews living in Poland at this time. I was certainly surprised at the extent of the JDC’s operations in Poland, particularly from 1958-1960. This story shows that every historical moment is contingent. It was not necessarily foregone that Poland would become, as it is today, about 97 percent ethnic Polish. Even in the 1950s, Jewish groups, communities, and individuals were debating the nature of Polish Jewry and its possibility for safety and inclusion in Poland. For some Jews, this inclusion was based in socialist activism, yet there were myriad other reasons Jews lived in Poland in this time. By the end of the period I examined in my virtual lecture, rising political antisemitism led the majority of Polish Jews to emigrate. Instead of taking that outcome as inevitable, however, I believe consideration of this period shows the development of exclusionary nationalism and the limits of liberalization in Poland after Stalinism. This in turn sheds light on contemporary democratic failures in Poland and abroad.

Q: What did your research at the JDC Archives reveal about the role and activities of JDC in Poland during that time?

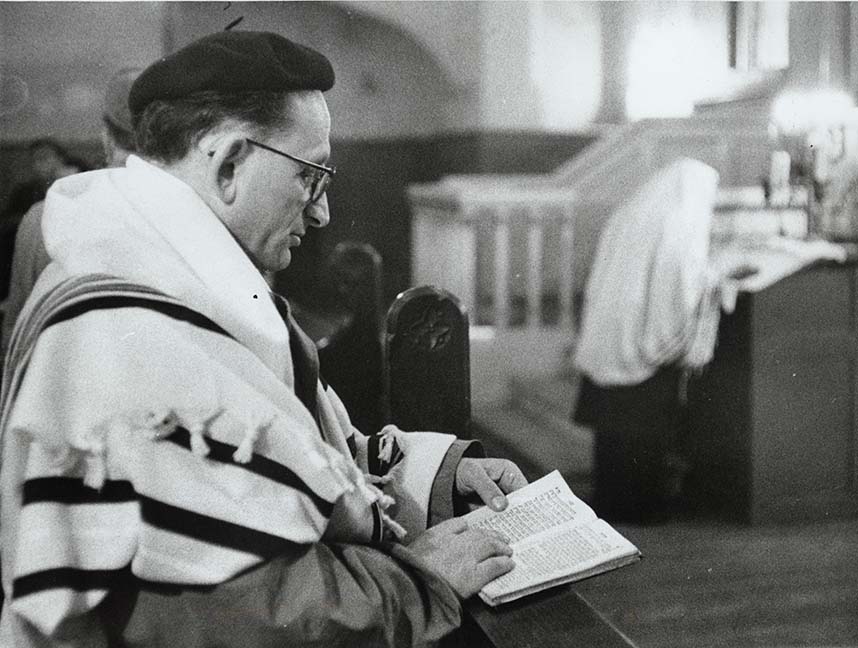

A: During the course of my research, I discovered that the JDC had extensive operations within Poland after 1957. These activities facilitated a revitalization of sorts for Jewish culture in Poland during this period, as the organization funded cultural events like concerts and theater, supported community centers, old-age homes, and orphanages, and funded religious leaders and ceremonies. Though the JDC at first worked well with local Polish Jewish groups, like the Socio-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ), as they shared the goal of aiding Jewish repatriates from the Soviet Union, these groups came into sustained conflict by the end of the decade. The JDC’s goal became prioritizing Jewish emigration, while local Jewish groups focused on building Jewish cooperative workshops within Poland.

These different visions of the Polish Jewish future reveal conflicting priorities and personalities, reflecting the dynamism of the period. The JDC and local groups were constantly in contention—born out of earnestness, fear, and hope for the future. These groups recognized this moment as a turning point, and though they ultimately had differing visions, they were able to come together in a moment of crisis and, in that way, leave their mark on Polish Jewish history.

Q: Did you find anything during your research in the JDC Archives that surprised you?

A: I was surprised by how expressive JDC officials were in their intra-office correspondence! I had previously worked with Polish archives, and official materials from this period are generally less colorful and more bureaucratic. In their official memos and letters, JDC leaders would comment candidly on the situation in Poland and on the personalities of Polish Jewish officials. For example, one JDC official wrote, “I, personally, would not trust [the TSKŻ leadership] as far as I could throw a 20 ton piece of ingot steel.” These archival materials gave me truly unique insight into the day-to-day operations of the JDC in Poland, the interpersonal challenges of relief work, and the optimism and heartbreaks of this period in Polish Jewish history.

Q: A related question: did you find anything in the JDC Archives that might lead to a new project?

A: The JDC Archives has a large collection of material related to this period in Poland. For the purposes of my dissertation, I focused on the period around the Thaw from 1957 to the early 1960s, yet I found rich materials related to 1962-67. As I consider future projects, I would like to pursue a longer-term exploration of the JDC in postwar Poland through its second expulsion in 1967 and to the present. I believe such a project would provide a more nuanced look at the development of nationalism and antisemitism in the context of the 1968 anti-Zionist campaign.

Q: Do you have any tips for scholars just beginning their research in the JDC archives?

A: On a technical level, do not rely too heavily on the search engine! Though the database has a wonderful search mechanism, some of the most enriching and unexpected materials I found were ones I would not have searched for. If you have time, try going through subcollections one by one.

The JDC Archives have a large collection of material—and wonderful finding aids and archivist support. Do not be afraid to dive in and ask for help!