A Wretched Voyage with a Happy End: The Story of the Cabo de Buena Esperanza and Cabo de Hornos

Refugees found sanctuary in Curaçao after ten-month ordeal

By Jeffrey Edelstein, Digital Initiatives Manager

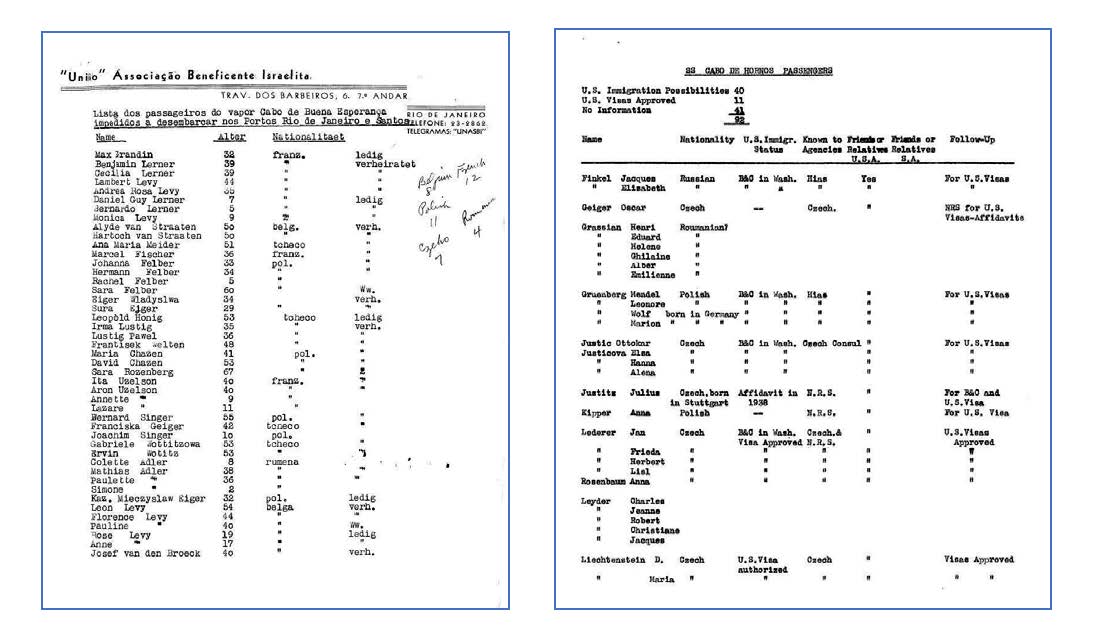

When selecting lists to be added to the JDC Archives Names Index, we often focus on the number of names included and the value of the information provided (place and date of birth, destination, accompanying family members, etc.). Sometimes, however, the story behind a list is so captivating that we feel compelled to add it to our database.

Such is the case with a set of lists of passengers on the SS Cabo de Buena Esperanza and its sister ship the SS Cabo de Hornos (Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn). Both ships made numerous sailings during the war, generally from Lisbon to South America, but it is a particularly harrowing voyage in 1941 that sparked attention around the world.

An entire folder in the New York 1933-1944 collection is devoted to the journey, which, according to a summary document found therein, unfolded as follows. In January 1941, a group of refugees with valid Brazilian visas left Marseille bound for Rio de Janeiro on a ship called the Alsina. When the ship made an initial stop at Dakar, Senegal, the Vichy government revoked its permission to continue its voyage. The ship remained there for four months, with the passengers confined aboard.

Finally in June, the Alsina was allowed to leave Dakar. It turned back to Casablanca, Morocco, where the passengers were incarcerated in a concentration camp. After several months, the Vichy authorities agreed to release a group of about 40 passengers, who would now leave for South America on the Cabo de Buena Esperanza from Cadiz, Spain. But by then they faced a new barrier: their original 90-day Brazilian visas had expired. Without valid visas for Brazil, they also could not be issued the Spanish transit visas they would need to depart from Cadiz. After considerable effort and negotiations between the various authorities—Brazilian, Vichy French, and Spanish—the passengers were able to proceed to Brazil. By now it was October.

Having survived months of confinement on the Alsina and the poor conditions of the Moroccan concentration camp, the group now faced new degradation aboard the Cabo de Bueno Esperanza. A December 1, 1941, article in TIME magazine paints a grim picture, reporting that the Cabo ships were noted for “the filth, crowding, misery and disease inside their hulls.” The article continues:

“The whole ship stank, the food was nauseous, the ship’s hospital used dirty newspapers for sheets. On the slow voyage across the Atlantic, two more refugees died.”

—“High Seas: Whited Sepulcher,” TIME, December 1, 1941, 30

The injustice and mistreatment did not end with the Buena Esperanza’s arrival in Rio de Janeiro. Local authorities disavowed the renewed visas and refused to allow the refugees ashore. The ship headed south to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Following emergency efforts by the JDC, the Argentine government permitted the refugees to disembark for a maximum of 90 days, but confined them to its immigrant station, with a JDC guarantee for maintenance costs.

Before the 90 days had expired, the Argentine government reversed itself, stating that the refugees would be deported. By then, Paraguayan visas had been obtained for the refugees, but the Argentine authorities refused to allow them to cross Buenos Aires to take the river boat to Paraguay. The group now numbered more than 80, as more former Alsina passengers, also denied permission to land by Brazil and now Argentina, had arrived on the Buena Esperanza’s sister ship, the Cabo de Hornos.

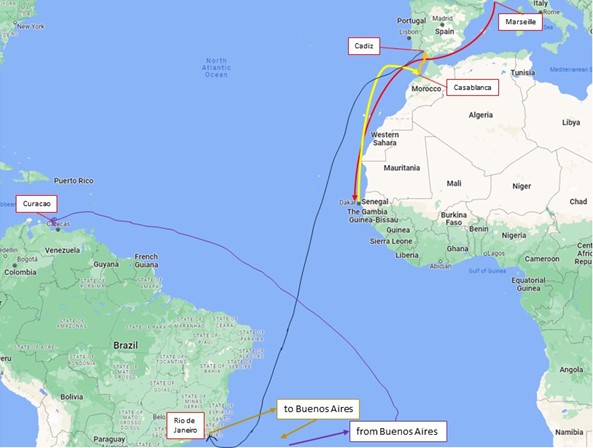

The journey of the refugee passengers, leaving from Marseille in January 1941 on the Alsina and stopping at Dakar, Senegal (red arrow), where they were detained aboard ship; then transferred to Casablanca, Morocco, where they were interned in camps (yellow); released and able to arrange new passage from Cádiz, Spain (gold) aboard the Cabo de Esperanza to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (black); denied entry and traveling on to Buenos Aires, Argentina (brown); told they would be returned to Europe on the Cabo de Hornos, but finally allowed a temporary safe haven in Curaçao (purple), arriving in November 1941, ten months after they had embarked.

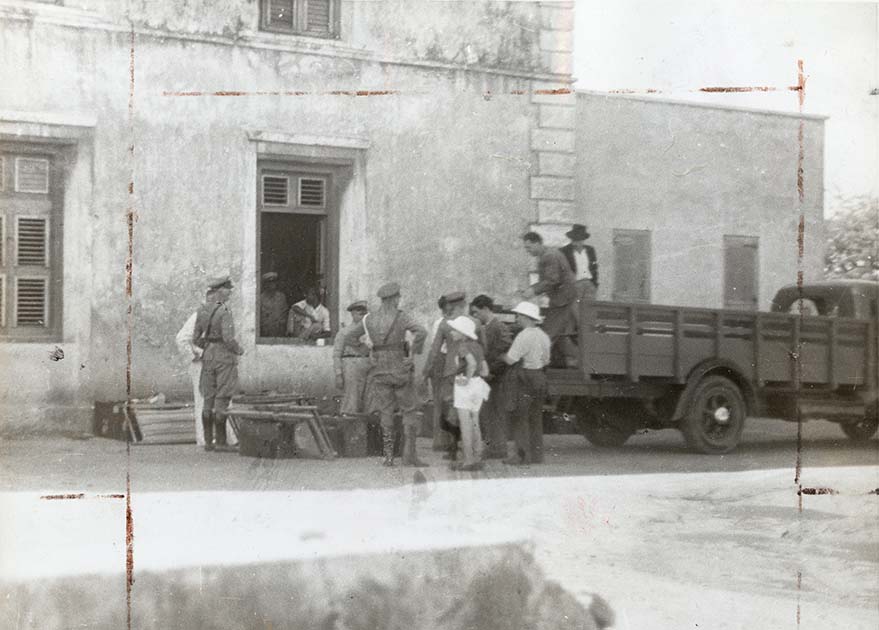

The passengers were now headed back to Europe on the return trip of the Cabo de Hornos unless a sanctuary could be found. At the very last instant and after intense diplomatic negotiations, on Nov. 19, 1941, the Dutch Government in Exile agreed to let the refugees land in its Caribbean colony of Curaçao for 90 days, on the strength of an agreement with the JDC. The JDC shouldered responsibility for the costs of maintenance and for finding the refugees permanent homes elsewhere.

Refugees who had just disembarked from the Cabo de Hornos arriving in Curaçao and being taken to their quarters, formerly temporary housing for foreign Royal Dutch Shell oil workers. Curaçao, 1941. JDC Archives

Within a short time, several dozen secured permission to enter the United States or Cuba, but when the 90-day deadline had expired, about 50 refugees still remained in residence. Their numbers continued to diminish as each family was able to leave; only about a dozen stayed on the island for the duration of the war. They were housed in camps under curfew and other restrictions that limited their freedom.

Some months ago, the JDC Archives received an email from Ron Gomes Casseres, a leader of Curaçao’s historic Mikvé Israel-Emanuel community, the oldest Jewish community in continuous existence in the Americas. As it happens, he had written an article, “The Saga of Cabo de Hornos: Fleeing the Horrors of War,” published by the National Archives of Curaçao in the November 2022 issue of its journal Lantèrnu. With clarity and precision and based on extensive research, Ron lays out the entire story, adding considerable detail about the situation in Curaçao, including legal and political factors as well as the community’s response. The article is followed by a companion piece by Jos Rozenburg, “The 86 Refugees, Who Were They and What Happened to Them after Their Arrival?,” which supplements the data in the JDC Archives Names Index records with specific dates and places of birth and information on when the refugees left Curaçao and their countries of destination. In addition to the United States, these countries included Colombia, Cuba, and Venezuela.

A name on a list can be just the beginning of the story!

Explore the Lists in the Names Index and Genealogy blog posts.