From Europe to Israel to Germany to Brazil

Using the JDC Archives, Samuel Kilsztajn tells his story and the history of the Israeli returnees to Germany and how they came to Brazil.

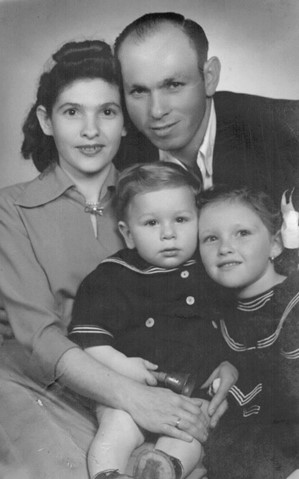

I started writing the story of my parents, both Holocaust survivors, only after they had passed away. Of course, the JDC was part of my parents’ history, as it is part of the history of all Jewish survivors who affectionately called it “the Joint.”

In December 2020, I wrote a short piece about my parents’ friends and sent it to their descendants, and it was very well received. It was then that I realized that everyone had taken the same Europe-Israel-Germany-Brazil route. I knew that my family, before arriving in Brazil in 1953, was housed in the Main Orthodox Synagogue in Munich and that my father was arrested because we didn’t have an entry visa for Germany, let alone for the United States, which was our destination. So, I started doing some research.

I contacted the JDC Archives and Senior Archivist Misha Mitsel kindly sent me links to many documents about the situation created by returnees who left Israel, and many lists of immigrants who arrived in Brazil. It was then that I started to write the history of the Israelis stranded in Europe that fate brought to Brazil.

They were Jews from Central and Eastern Europe, mostly Poles, who survived the Holocaust in Nazi forced labor and concentration camps, or in Siberia and other parts of the Soviet Union. They lost their parents, family, houses, cities, and homelands. In the postwar period they were housed in DP Camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy, many immigrating to the newly created State of Israel. However, there were those who were dissatisfied with their life there. Armed with Israeli passports, some returnees left Israel in the 1950s to immigrate elsewhere. Before they did so, they returned to Germany to await their visas and transfer to the United States or Canada, but ended up in Brazil instead, more precisely in São Paulo, where the returnees found their Bom Retiro, or “good retreat.” Returnees to Europe started to arrive as early as August 1949—among their reasons for leaving were climate, poor health, separation from their families, poverty, war, and their inability “to meet pioneering conditions.”

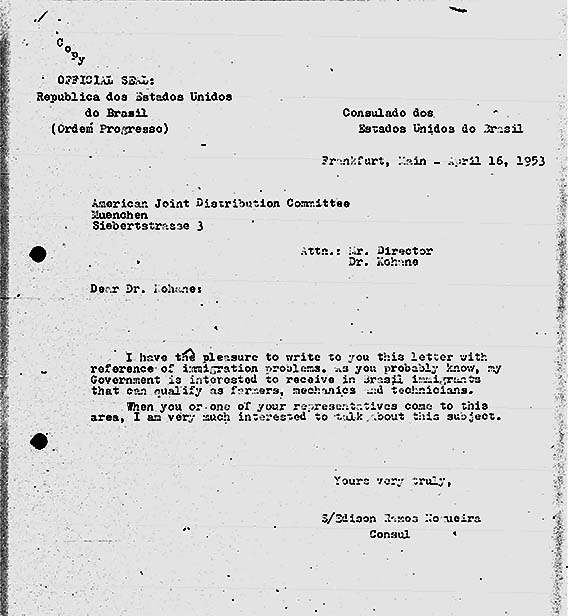

In a correspondence dated April 16, 1953, Edison Ramos Nogueira, Brazilian consul in Frankfurt am Main, invited Akiva Kohane, representative of the Joint in Munich, to discuss Jewish immigration. After discussions between Nogueira and the Joint, a large contingent of Jews was permanently admitted to Brazil in August 1953, regardless of their professional qualifications.

While the earliest of these returnees ended up back in the Fohrenwald DP camp, the camp had to be closed off to newcomers as those numbers swelled. In October 1953, some of those who could not get into Fohrenwald occupied the Orthodox synagogue in Munich. While they were there, JDC provided money for food, medication, clothing, and other assistance. On November 4, 1953, the 67 men among the 150 Israelis who were occupying the synagogue were arrested as they did not have legal entry visas for Germany, including my father.

In December 1953, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) arranged and paid for transport and accommodation for some of these returnees to Brazil. And here I was, Samuel Kilsztajn, son of Polish Jewish survivors, born in Israel on July 9, 1951, housed in (and displaced from) the Munich Orthodox Synagogue, and then passenger on the French transatlantic SS Claude Bernard, who disembarked at the Port of Santos on December 19, 1953.

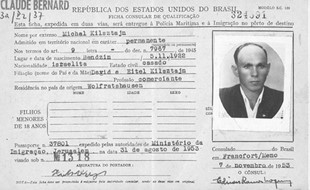

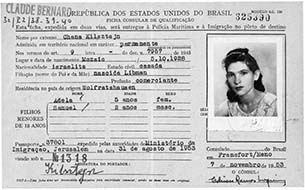

Immigration cards for Samuel’s parents, Michal and Chana Kilsztajn.

However, for Jewish organizations in Brazil, there was a significant difference between receiving Holocaust survivors who arrived directly from Europe or through South America and receiving the Holocaust survivors who arrived from Israel, who some considered to be abandoning the Jewish state that many had so longed for after the atrocities that took place in Europe. Nonetheless, the Joint continued to support returnees’ immigration to Brazil. On April 14, 1954, Julius Lomnitz, director of the Joint for Latin America, declared that immigration of returnees to Brazil was adopted with the approval of the Government of Israel and the Jewish Agency of Israel, and that Brazil was the only country other than Israel that was accepting returnees who could no longer remain in Germany.

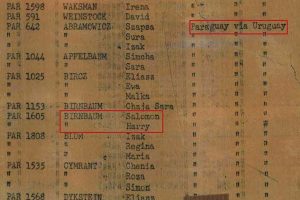

More than 18,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors immigrated to Brazil between 1945 and 1959. The names of some Israeli immigrants to Brazil in 1953-54 were collected from sparse lists and letters from the JDC Archives. These survivors who wandered Europe and lived in Israel were fascinated with Brazil, the country that welcomed them. The Brazilians’ joy was contagious, everyone was good, communicative, and affable. It was a paradise for those who had left the Old for the New World, Di Naye Velt. People received them with open arms, despite the previously declared antisemitism of the country’s political elites. Although they remained supporters of Israel and continued to maintain strong ties with close relatives who were still living there, practically all these Wandering Jews permanently settled in Brazil, where their difference was not punished and where they left their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Explore your own family history in the JDC Archives Names Index.

About the Author

Samuel Kilsztajn is a professor of Political Economy living in Brazil and is doing research on the life of his family, Polish Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. This story is shared with his permission.