Life in Sosúa Revealed

Detailed logbooks illustrate the daily life of Jewish refugees in the Dominican Republic

After the Dominican Republic offered to take in refugees following the Evian Conference in 1938, JDC founded the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA), which established an agricultural settlement for over 700 Jewish refugees in Sosúa. But how did these German Jewish refugees transition from city dwellers to farmers on a distant island?

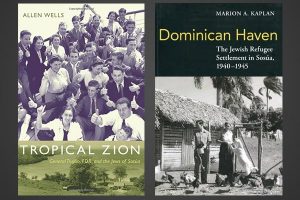

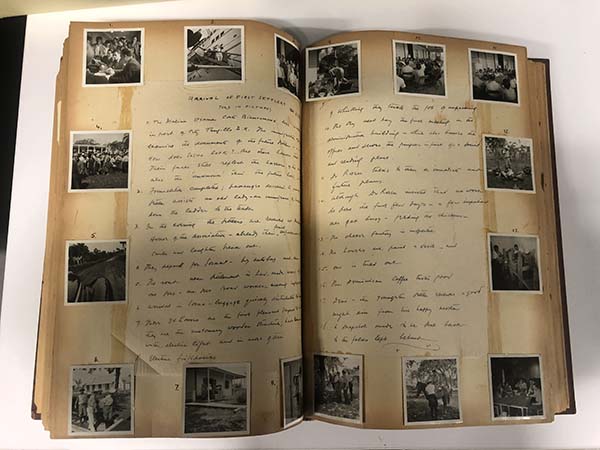

Revealing insights about life on Sosúa can be found in two logbooks in the JDC Archives. These scrapbooks, overflowing with photos, reports, correspondence, journal entries, blueprints, diagrams, and lists, meticulously log all details of daily life in the farming community. Furthermore, all pages of the logbooks are hand assembled, their collage effect more likened to a work of art than simple reports. This helps to provide a window into the workings of DORSA’s management team of colonization experts in New York and on the island, who oversaw the operations of the settlement itself. JDC’s then Vice President James N. Rosenberg, along with Dr. Joseph Rosen, brought a wealth of experience to the project. In fact, Dr. Rosen had been the Director of Agro-Joint, a venture that had settled Jews in agricultural colonies in the Ukraine and Crimea beginning in 1924, and directly supervised farm settlement there.

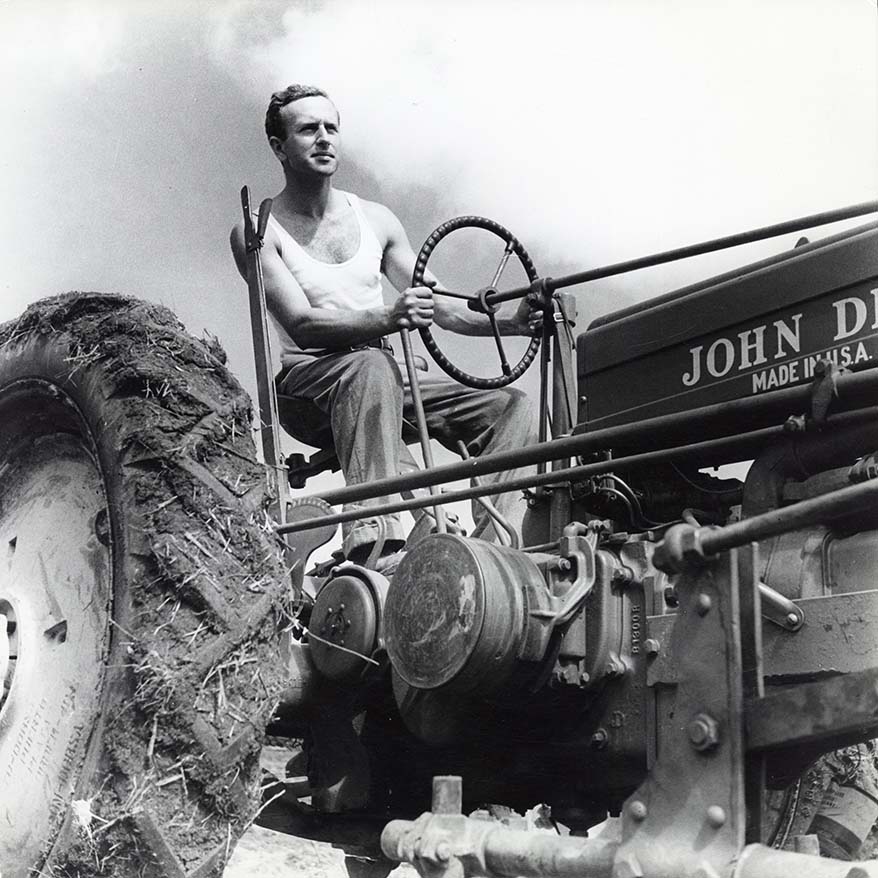

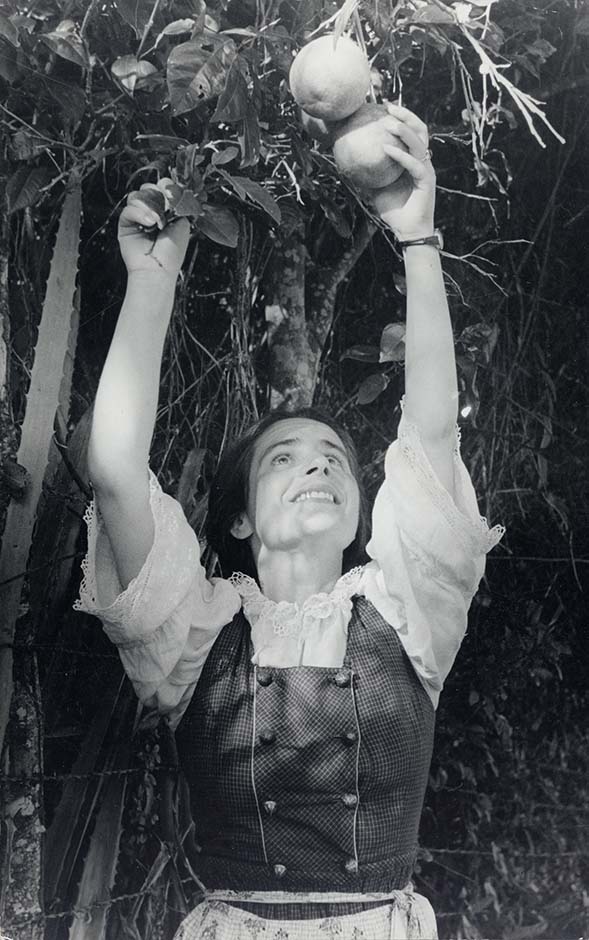

Some entries are heartwarming and hopeful like the two pages that record the arrival of the first settlers in May 1940. Their welcome is told in images, with a perimeter of photographs framing the corresponding handwritten captions, providing an intimate portrayal of the event. As settlers acclimate to their new surroundings, entries tell of Sosúa’s agricultural possibilities. For example, one passage reports that “the site of the settlement is well selected, yet colonists prefer mechanized labor to manual labor”- not surprising for the transplanted farmers. The experts knew that sanitation and a suitable diet were chief concerns for colonists and considered farming “mangos, pineapples, coconuts, and tropical vegetables, like pigeon peas,” with the prospect of selling goods to the American market. Their desire to secure colonists’ well-being, both physically and financially, is apparent.

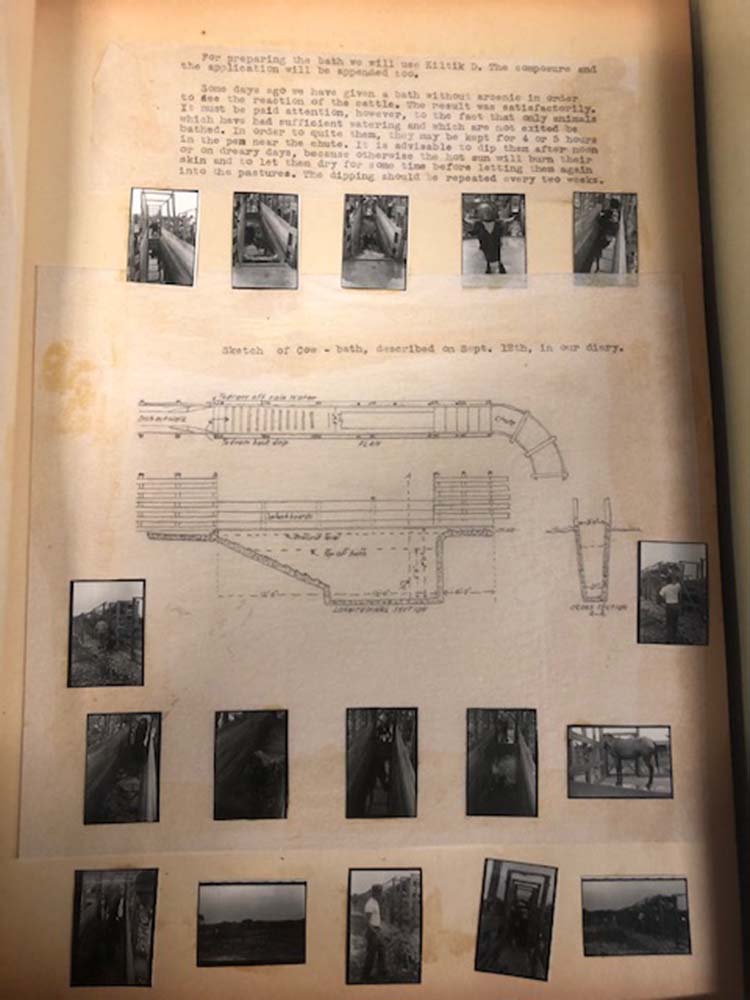

The thoroughness of the accounts also illustrates the dedication present in Sosúa. The journals disclose a plethora of daily happenings, from the planting arrangements in the gardens to the daily egg count of hens. One can read about construction plans, milk and cheese production, seasonal rainfall and temperature, as well as food supply and the types of livestock that roamed the fields. In one entry, the number of cattle, pigs, horses, mules, and donkeys are listed, down to the loss of one cow who was sadly poisoned by a plant. Such missteps were a constant reminder that farming a Caribbean island was completely new territory for settlers.

Though the transition was a difficult adjustment for the transplanted Europeans, the settlement did manage to have a successful dairy cooperative. Despite the obvious obstacles of fickle terrain and uprooted civilians turned unskilled farmers, most striking when leafing through these logbooks is the industry and perseverance exhibited in the face of war and exile. This is evident with both the range of work undertaken in the settlement and the painstaking efforts to document the enterprise. Eventually, by war’s end the commune dissolved, and most Jewish refugees emigrated to the United States and elsewhere. However, their lives in Sosúa are memorialized in these logbooks, which provide incredible historical accounts for those interested in this little-known period of Jewish history.

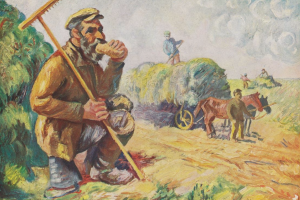

Plowing the fields, Sosua, Dominican Republic, 1940s. Photograph: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado.

Explore the finding aid of the Records of the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA) to learn more, and view more photos of life in the Dominican Republic during World War II.