Lists of Shanghai Repatriates to Austria and Germany Indexed

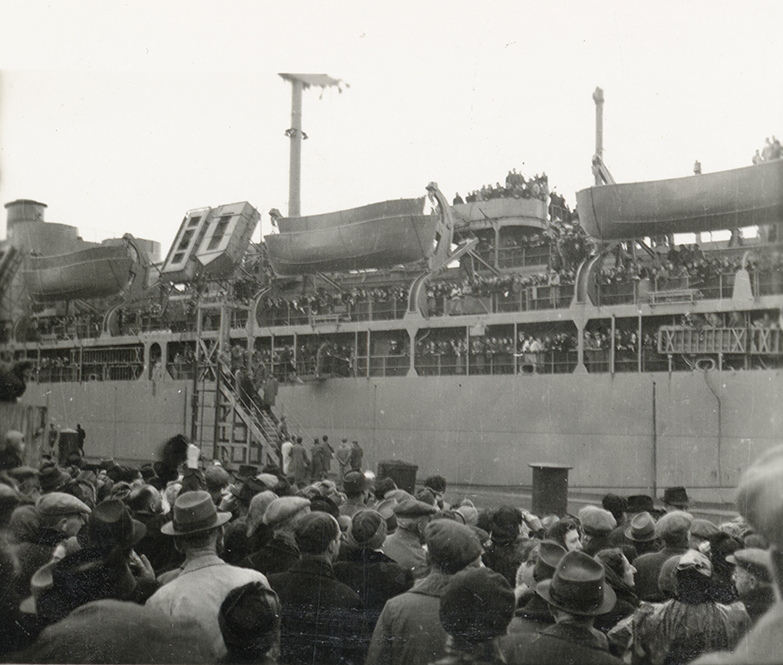

Thousands of Jews survived World War II in China with JDC aid

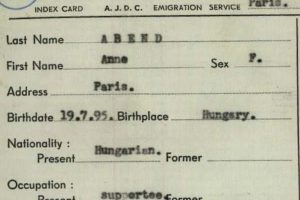

Two lists of repatriates from Shanghai to Austria and Germany have recently been added to the JDC Archives Names Index. The lists, from 1947, were among the digital files of JDC documents received from the Arolsen Archives (formerly the International Tracing Service; ITS). JDC had deposited these files with the ITS when JDC’s own post-World War II tracing activity ceased.

Most of the over 17,000 Jewish refugees in World War II Shanghai fled Germany and Austria in 1938-1939, after the Nazi Anschluss (see topic guide “Refuge in Shanghai,” for further information). As an open international city, Shanghai was one of the only options for those who could not obtain visas for other countries. JDC provided essential support, working through local organizations such as the Committee for the Assistance of European Jewish Refugees in Shanghai, which was organized in 1938.

Virtually all the Jewish refugees saw Shanghai as a temporary wartime refuge. Once the war ended, they sought to move on with their lives in more permanent locations. As Professor Fred Lazin, who conducted extensive research on this topic in the JDC Archives, has noted, JDC surveyed more than 12,000 refugees, asking them where they preferred to emigrate; the results were 39 percent for the United States; 19 percent for Australia; and 8 percent for Palestine. But perhaps surprisingly, given ongoing antisemitism in their former home countries, 16 percent said they preferred repatriation.

The reasons for repatriation were individual and varied. As both Lazin and Elizabeth Anthony, in her book The Compromise of Return: Viennese Jews after the Holocaust, 2021; see book review) point out, U.S. quotas remained strict, limiting the number who could gain entry to the United States. Immigration to Palestine, still under British Mandate, was also limited before 1948, and for many, Palestine was not an appealing option. Based on the dates of birth included on both lists, it is clear that many of the repatriates were older; Anthony states that repatriation of this group reflects “more mature survivors’ desire to live in a familiar place and refusal to start over again in yet another foreign country. Many did not see a future anywhere else” (p. 194). She continues, “Many simply failed to conceive of another place in which they might professionally or socially begin again due to challenges of age, language, or immigration restrictions” (p. 195).

Others may have hoped that their chances to immigrate to the United States or elsewhere would be greater from Europe than they were from Shanghai. In a March 28, 1946, letter to JDC Overseas Director Joseph Schwartz, Executive Vice Chairman Moses Leavitt states,

Some 1,400 Jews in Shanghai have registered for repatriation to Vienna. Bad as the situation may be in Vienna, you can readily imagine that it is much worse in Shanghai. The chances for reemigration from Vienna are considerably greater than they ever will be from Shanghai. On that basis alone we ought not to press that the people stay on and not opt for repatriation and not give them some alternative solution to their problem in Shanghai.

Repatriation was the responsibility of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) until it was dissolved in September 1948, as noted in a memo of May 21, 1947, from JDC Assistant Secretary Melvin Goldstein to the JDC Emigration Department. JDC remained actively involved, however, assisting UNRRA with documentation and technical services for JDC welfare clients and providing basic support to the repatriates when they returned to their home countries. The provision of housing is one example; as JDC representative in Vienna J.S. Silber reports, “arrangements were finally made whereby some reasonable housing accommodations were made available to all those requiring the same” (memo to AJDC Paris, February 15, 1947). Other repatriates went to the displaced persons camps prior to further emigration.

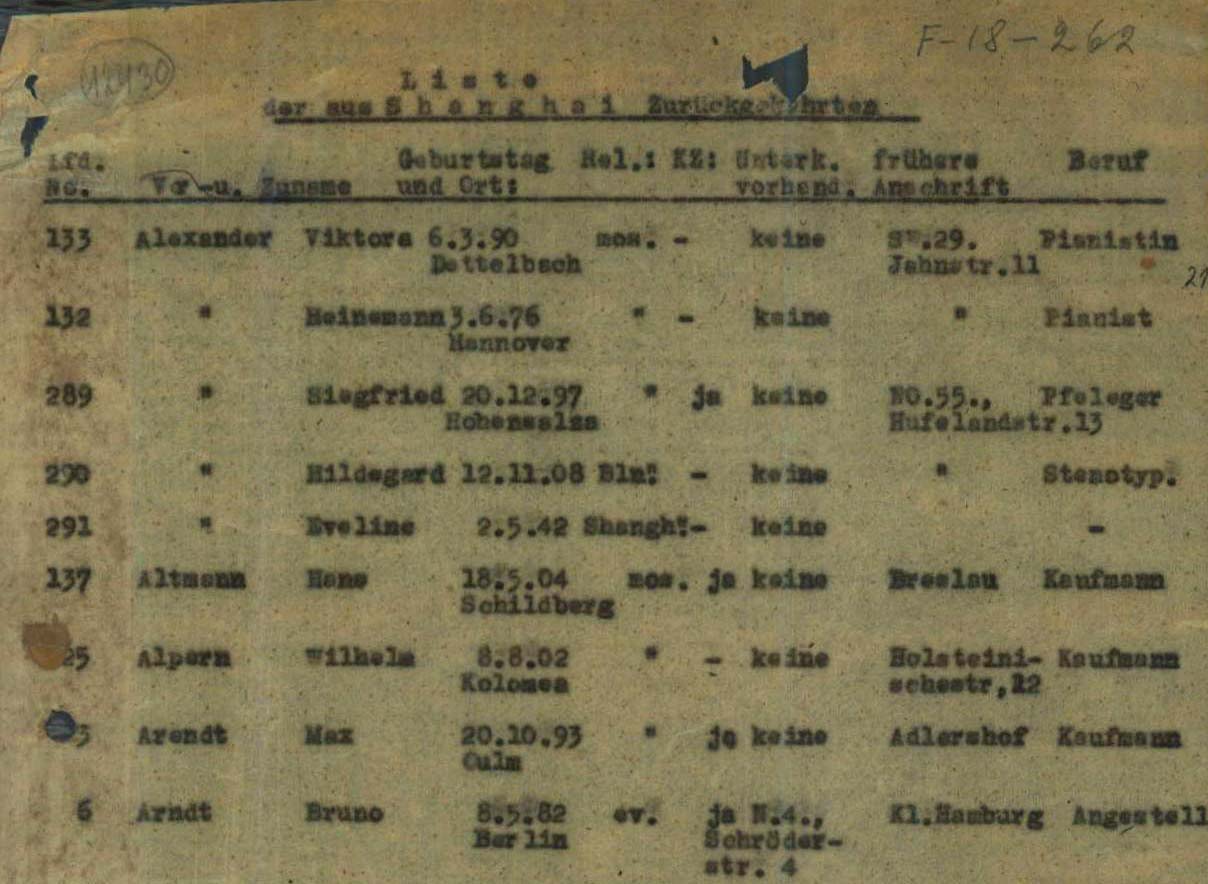

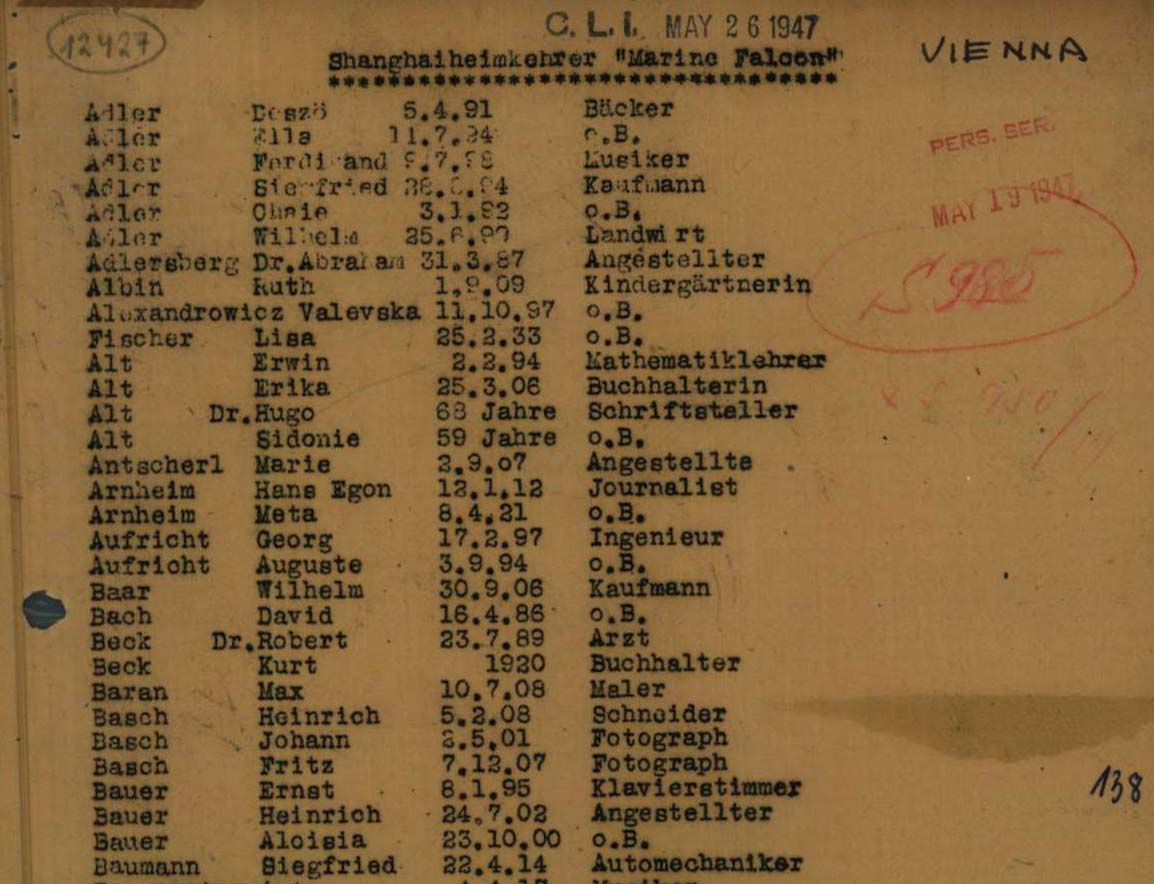

Sample pages from the lists of Shanghai repatriates to Germany and Austria (click to enlarge).

Both lists date from 1947 and, depending on the list, provide various personal details such as date and place of birth, eventual address, and occupation. The list of repatriates to Austria is in fact three separate lists of passengers returning to Vienna on the S.S. Marine Falcon, Marechal Joffre, and Marine Lynx. The list of German repatriates documents all those who had returned from China as of September 9, 1947.

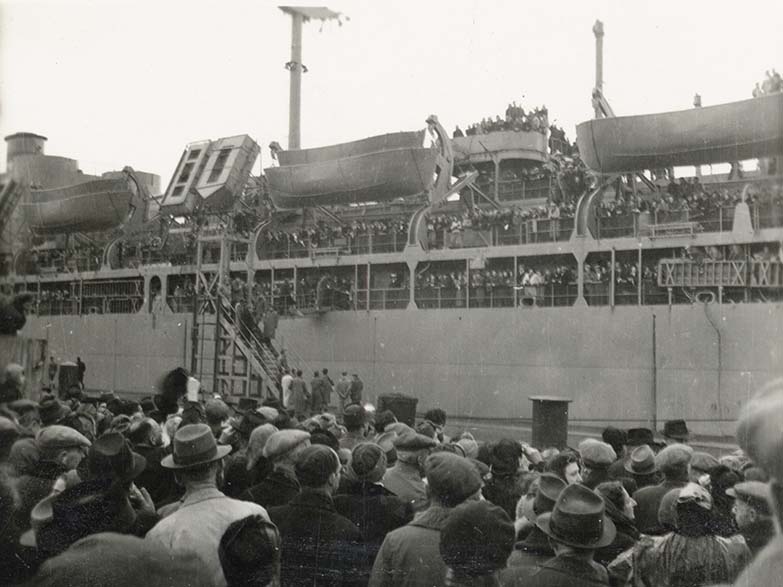

By 1949, Communist forces were closing in on the city and more than ever, the refugees needed to leave. Although many were able to go to the United States and Australia, quotas remained tight. Meanwhile, the end of the British Mandate and establishment of the state of Israel made it an easier option; for some, it was the only option. Many of these refugees had no papers, making it difficult to gain entry to any other country. JDC, working in cooperation with the International Refugee Organization (IRO), continued its efforts to help the refugees leave Shanghai. Several trips transported the refugees first to San Francisco by ship, then across the United States in sealed trains until reaching the East Coast, where they then reembarked on ships to Israel.

One notable incident related to this transportation system that involved repatriates took place in May 1950. The refugees had hoped to remain in the United States, and a new displaced persons act that might have made them eligible was due to become law only two to three weeks after their arrival in San Francisco. The situation was discussed at a May 18, 1950, meeting of JDC’s Committee on Immigration Matters, with a decision to participate in an appeal to the U.S. government by Jewish agencies to request a temporary stay (see meeting minutes). Nevertheless, the group was transported on sealed trains and repatriated to Germany. On their arrival in Bremerhaven, they were greeted by Charles Jordan, JDC European Emigration Director, known to many of the repatriates as the former head of JDC’s office in Shanghai. Jordan was there to offer further assistance, including the possibility that JDC could help them through the bureaucratic hurdles to gain entry to the United States.

View a photo gallery of Jewish refugees in wartime Shanghai and explore Shanghai records and more in the JDC Archives Names Index.