New Book—Hitler’s Jewish Refugees: Hope and Anxiety in Portugal

Between a lost past and an unpredictable future

While historians have investigated how Jews escaped Nazi Europe, few have examined how refugees were emotionally affected by their odyssey. It is this gap that Dr. Marion Kaplan’s highly readable new book, Hitler’s Jewish Refugees: Hope and Anxiety in Portugal, seeks to fill. Using the memoires, diaries, and letters of refugees, Dr. Kaplan, Professor of Modern Jewish History at New York University, attempts to understand how refugees felt during their flight to Portugal and their stay there. Throughout the book, she transcribes the anxiety felt by the refugees, who desperately needed to flee Nazi-occupied Europe and were anxiously waiting to immigrate to other countries.

During the war, Portugal emerged as the best way station to escape Europe for North and South America. Kaplan notes that refugees arrived in several waves, each of which had a different experience. The first wave, which arrived between 1933 and 1939, was made up of several hundred German and Austrian Jews fleeing Nazi Germany’s increasing persecution. Armed with proper documentation, they came directly from their home country and did not face as many hurdles as the refugees who arrived after the outbreak of World War II. A number of these earlier refugees had relatives in Portugal who facilitated their immigration and eased their transition financially and emotionally. Most had some financial means as the Portuguese government allowed in only the refugees with the capital or skills to live there. Those without wealth or family ties turned to the small Jewish community for economic and moral support. While some left, others settled in and founded businesses. They faced the usual challenges of newcomers—getting the permission to remain, finding jobs or starting new businesses, learning a new language—but they remained hopeful.

The second and third groups of Jewish refugees who fled to Portugal numbered around 70,000 and 10,000 respectively. The second group came after Germany defeated France in June 1940, while the third arrived in the fall 1942 after Germany occupied Southern France. Prior to their arrival in Portugal, the refugees in these groups had already been transmigrants in France, Belgium, or Holland. While fleeing the advancing German army, they had experienced the long lines at the consulates to obtain the necessary papers, the ever-changing immigration rules of Nazi Germany, and the unpredictability of Spanish and Portuguese border guards, who could send them back to Nazi-occupied Europe. Unable to get the proper visas, some had to use forged visas and cross the Pyrenees with the help of smugglers.

Even after they reached safety in Portugal, Jewish refugees continued to experience emotional turmoil as they waited anxiously to immigrate to North and South America. The dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar provided a reluctant haven to refugees, pushing them to leave but allowing the small Jewish community and international groups, such as JDC, to assist them. In cooperation with the Lisbon Jewish community and the Quakers, the Joint provided refugees with subsidies, rent, meals, clothing, medicine, and religious necessities such as matzot for Passover. It helped those who had arrived illegally to acquire the necessary papers. In addition, the Joint purchased ship tickets or even chartered ships on its own. Dr. Kaplan points out that aid organizations such as the JDC “functioned as the unsung heroes” during this crisis. By paying for the refugees’ basic needs and assisting with food and ship tickets, they saved lives.

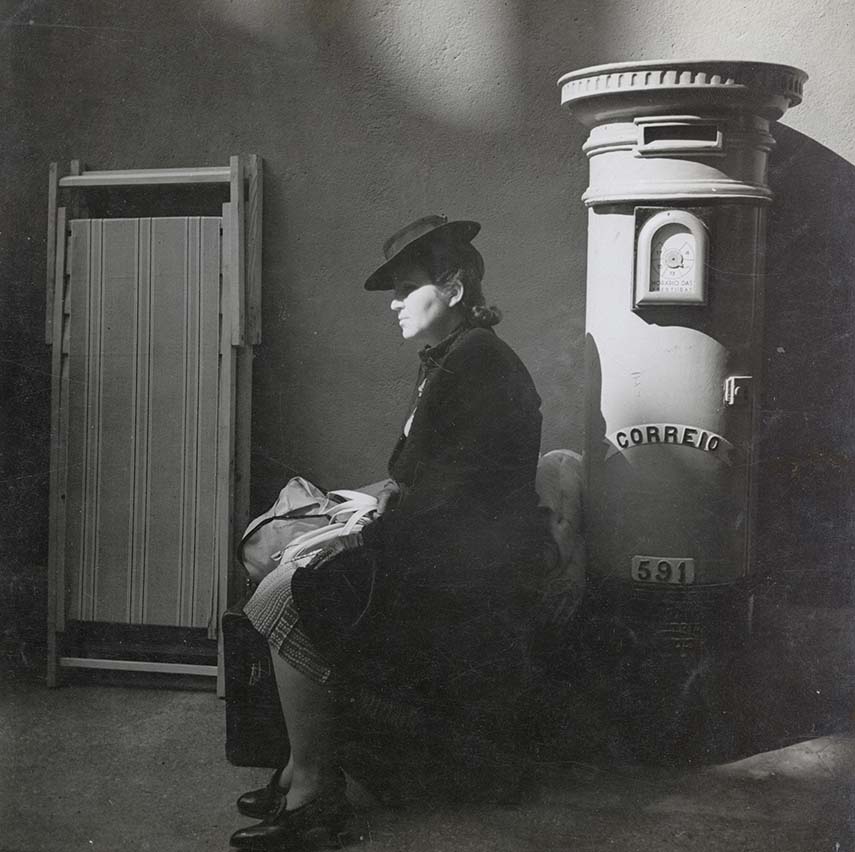

How did refugees respond to life in Portugal? Using numerous examples, Dr. Kaplan meticulously transcribes the anxiety and dejection they felt. The refugees were dismayed at the loss of their home, homeland, and previous middle-class life. Many felt that no countries wanted them. Dr. Kaplan’s cites one refugee, Hans Reichmann, who wrote, “We lost our footing…with no home…Every day tugged at my roots until they finally tore loose.” They found support by forming new friendships in cafes with other refugees and by writing letters to loved ones abroad. But cafes friendships were fleeting, and letters from loved ones could cause grief, especially when refugees learned of the fate of their families that had remained in Nazi-occupied Europe through the letters they received. Only visas and ship tickets to a new world could provide safety and relief.

Rich in detail and sources, Hitler’s Jewish Refugees is an important addition to the growing historical literature on the role of the Iberian Peninsula during the Holocaust.