New Book on Jewish Refugees and JDC in Warsaw during the Holocaust

January 6, 2017

“We appeal to your conscience and extend our hands to request aid. Please save us!”

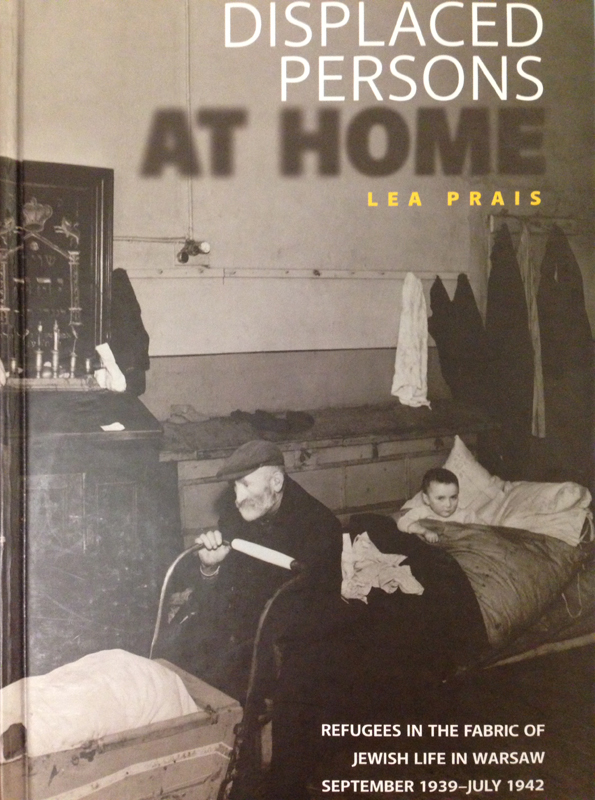

This plea for help from Polish Jewish expellees reached the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) office in Warsaw in June 1940. The words of these helpless Jews, who were expelled from their homes and hometowns, and forced to flee from one location to another within German-occupied Poland, present the desperate situation of displaced Jews during the Holocaust, and highlight the key role that JDC played for them. Thus, Dr. Lea Prais, a historian at the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem, used this quote to begin the discussion of JDC’s activities on behalf of the refugees. Prais’ book, Displaced Persons at Home: Refugees in the Fabric of Jewish Life in Warsaw, September 1939-July 1942 (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem Publications, 2015), an English translation from Hebrew, is a comprehensive and impressive study of the Jewish refugee experience in German-occupied Poland, and in Warsaw in particular, as well as of the organizations and institutions that aided the refugees.

Prais meticulously traces what she refers to as, the waves of the Jews’ escape, expulsion, and exile during the Nazi era. She zooms in on the reception, situation, and role of displaced Jews in Warsaw before and after the creation of the ghetto. JDC occupies an important place in that history, and the records of JDC’s Warsaw office from 1939 to 1941 offer invaluable sources for Prais’ study. From the beginning of the war until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, when JDC entered the war and was forced to formally cease its activities in Poland, JDC served as a lifeline for Jews in villages, towns, and cities, providing food, clothing, money, and shelter. The reports, lists of aid recipients, correspondence, and budgets illuminate the individuals involved in JDC’s work and offer details about the aid recipients themselves, as well as testify to the deteriorating situation of Polish Jews and the organization’s efforts to ameliorate it.

Displaced Persons at Home brings into the forefront the experiences of ordinary Jews from outside of the big urban centers. An analysis of the decisions that exiles made, of the enforced policies, and the responses of Jewish leadership and Jewish communities to the plight of their coreligionists train a powerful lens on local history. Here, the refugees are the agents, and not just aid recipients. They are the carriers of information about Nazi policies and actions. They are the bearers of the history and memory of their destroyed communities. But their maintenance once in Warsaw poses serious constraints for the city’s Jews, already overwhelmed with individual and communal needs. Refugees thus become sources of friction.

The staggering number of refugees in Warsaw – 150,000 between September 1939 and July 1942 among a Jewish population of some 450,000 – overwhelmingly relied on external assistance. Faced with housing shortages in the ghetto, these Jews lived in overcrowded and disease-ridden hostels. Their only hope lay in Jewish organizations, such as JDC and Landsmanschaftn. Prais writes about the role of the JDC-created “Public Sector,” headed by Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum, a JDC staff member who later was the leader of the Oyneg Shabes Secret Archive. This network of social workers and leaders coordinated relief efforts for refugees, often as their only hope for survival. But some refugees took their own initiative, seeking connections with their prewar and familial networks in Warsaw. Then too, depending on their place of origin and period of expulsion, a small number of refugees possessed enough to sustain themselves. Refugees were not a uniform group. And Prais carefully examines the variations in the refugees’ experiences and their implications for the larger Warsaw Jewish community.

Studying refugees during the Holocaust elucidates Nazi ideology and key anti-Jewish policies. It highlights the marginalized segments of society. And it illustrates how individuals and communities respond to the most helpless people. In her book, Displaced Persons at Home: Refugees in the Fabric of Jewish Life in Warsaw, September 1939-July 1942, Lea Prais has done a praiseworthy task of assigning a proper place for refugees in Holocaust historiography.