Uncovering Jewish History in Bolivia

For Len Bieber, researching the history of Jewish emigration to Bolivia against the backdrop of World War II is particularly resonant: he was born in Bolivia, to German Jewish parents. A professor of political science who has taught in Ecuador, Germany, and Mexico, in 2010, Bieber published Presencia juda en Bolivia: la ola inmigratoria de 1938-1940 (The Jewish Presence in Bolivia: The Immigration Wave of 1938-1940), where he examines the WWII-era wave of Jewish immigration to Bolivia and analyzes the factors which impacted their economic and sociocultural integration at that juncture.

The Jewish refugee experience in Bolivia was indelibly influenced by Maurice Hochschild, a wealthy German Jewish mine owner in Bolivia who had a good relationship with the Bolivian president. When the Bolivian government encouraged immigration in the mid-1930s to spur the economy, Hochschild facilitated visas for German and Austrian Jewish refugees to arrive in Bolivia. He also founded the Sociedad de Proteccion a los Immigrantes Israelitas (SOPRO), or The Society for Protection of Migrants Israelites. The majority of Jews settled in La Paz, the capital, and JDC supported SOPRO childrens homes and other communal institutions in La Paz. View images of JDC relief in Bolivia here.

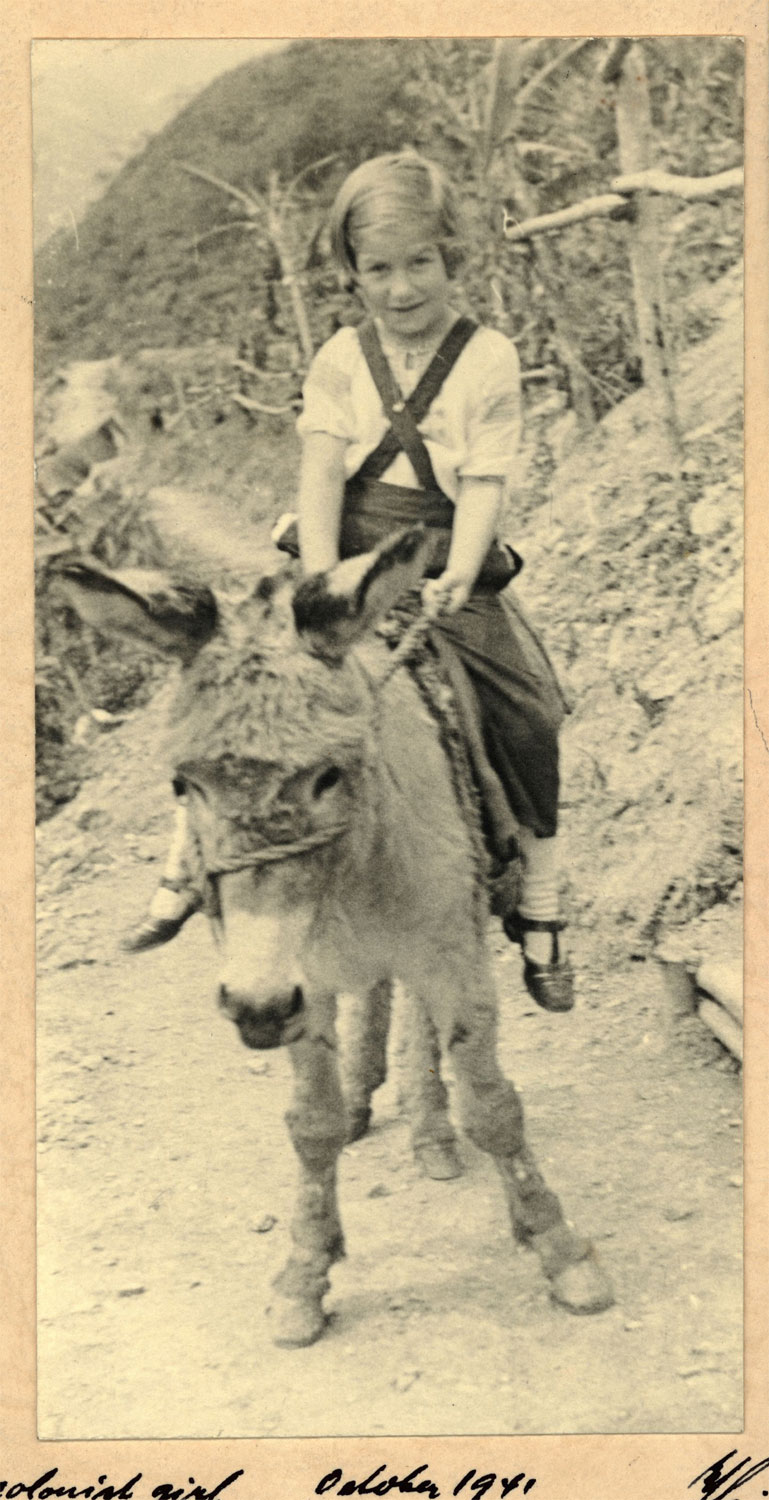

A young girl rides a burro in the Buena Tierra colony. Bolivia, 1941

In 1940, to counter rising anti-Semitic propaganda that Jewish immigrants were not contributing to the welfare of the state and to ensure that Bolivia would not close its doors to future Jewish immigration, Hochschild partnered with the Sociedad Colonizadora de Bolivia (SOCOBO) to develop agricultural projects in rural areas to demonstrate these Jewish refugees self-sufficiency.

Unfortunately, the new farmers encountered a host of challenges in their agricultural enterprises: the mountainous topography, which meant that they could not use tractors; the dearth of roads to appropriate markets for the crops such as pineapple coffee, and cacao; and the sub-tropical climate. None of the farms ever become entirely self-sufficient; they were all subsidized by SOCOBO and Hochschild.

Even as Bieber was aware of JDCs role as he researched this fascinating history, he was not aware of the extent of JDCs role until he began to grapple with additional questions which emerged during the course of writing his first book.

This book [Presencia juda en Bolivia] was full of questions I couldnt answer, he recounted.

And these questions led him to the records at JDC: It became clear to me that I could only find the answers if they exist in the archives of the Joint.

In the archives, Bieber discovered that Hochschild contacted JDC and Agro-Joint for funds to relocate Jews as peasant farmers and train them to cultivate the fields. From 1939-1942, JDC, along with SOCOBO and Hochschild, contributed $160,000 to sustain the agricultural settlements.

As Bieber uncovers additional information about the complex history of Bolivian Jews, including these agricultural enterprises, he intends to write another book: one which deals with the Joint, Hochschild, and the first wave of Jewish immigration to Bolivia. It is impossible to understand, he says, the documentation of the waves of Jewish immigration without the archives of the Joint.