Memories of Tehran

The evolution of life-saving packages and the man behind them.

A lesser-known tale of Holocaust survival entails the journey of Jews who fled to eastern Poland following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and lived out the war in the Soviet Union and Central Asia. Such is the story of George Landau and his family. However, thanks to the ingenuity of his father, Dr. Majer Landau, JDC was able to carry out a complex program whereby clothing, and food stuffs were shipped to Polish Jewish refugees living under extremely harsh conditions in Siberia and Central Asia.

From Tehran in January 1944, JDC launched an individual parcel service for Polish-Jewish refugees in Russia. The service continued until June 1946 via the Russian parcel post, and it was discontinued only when the bulk of the refugees began streaming back to Europe and other parts of the world. Under Majer’s guidance, 10,000 packages were sent out per month to refugees, eventually totalling 211,387 parcels forwarded via Tehran. In the later years, Jewish refugees in Asiatic Russia from the Baltic States also became beneficiaries. The JDC funded almost 60% of the project and handled the full administration of the service. The balance of the funds was contributed by the Jewish Agency, South African Jewry, the Polish Government-in-Exile London, and the Polish Red Cross. Dr. Majer Landau played an active role in this life-saving project, devising cost-efficient and innovative ways for JDC to send these packages of food and clothing to Jewish refugees.

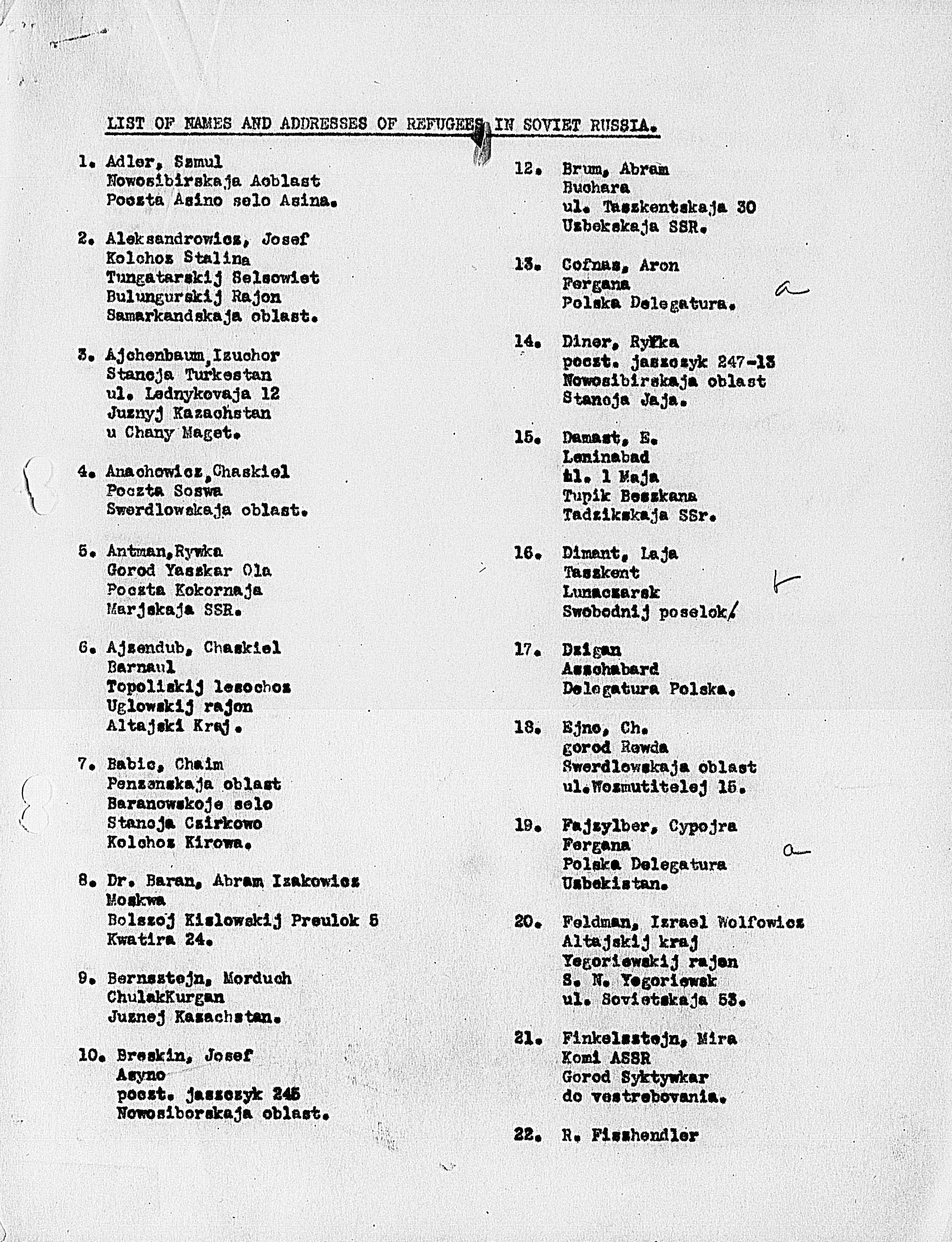

Page from a list of beneficiaries receiving packages in Soviet Russia. View more lists of beneficiaries of JDC’s free parcel service in the Soviet Union, 1943–1945. (JDC Archives; click image to enlarge)

A JDC Archives eNews editor interviewed Majer’s son, George Landau, about his father and the period in Tehran to get a firsthand account from George of how the Landau Family found themselves in Tehran, as well as the incredible role Dr. Majer Landau played in maintaining this package program.

Q: We would love to hear some background on your father’s experience. Where was he from originally, and what was your family’s odyssey during the war years?

A: My father was born on February 20th, 1898 in Mosciska, Poland (presently Mostyska, Ukraine). When World War II began in September 1939, the Soviet Union incorporated this part of Poland, and in the summer of 1940, my family, composed of my parents, my older brother, and I were deported from Lwow, Poland (presently Lviv, Ukraine) to Siberia. After German forces invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Soviet Union and the Polish Government-in-Exile signed a treaty whereby all former Polish citizens would be able to leave the Soviet gulags and special settlements. In Siberia, at a labor camp, my father undertook forced labor at 40 degrees below zero in the Siberian wilderness. When we were finally able to leave, I still well remember that feeling of freedom, finally being liberated from the camp. We departed Siberia and traveled to Uzbekistan, from which by a series of miracles we were able to leave on December 18th, 1943, to Iran. In April of 1945, my mother, brother, and I arrived in the USA. My father joined us in May of 1946, after a pit stop to Australia, where he visited his sister, whose assistance had allowed the family to leave the Soviet Union.

Q: Can you tell us briefly when and how your father connected with JDC in Iran?

A: When we arrived in Tehran at the end of December 1943, my father began to reach out to various agencies that could help us. Through the ‘Polish Delegatura,’ the underground representatives of the Polish government-in-exile, he was invited to meet with Dr. Ishay, a representative of the Jewish Agency. Dr. Ishay became very interested in my father’s opinions about what items people in Russia required in order to prolong their lives. They stayed in touch and in January 1944, my father was informed by Dr. Ishay that representatives of JDC had arrived in Tehran and were anxious to meet him. Soon thereafter, he met with Mr. Charles Passman and Mr. E. Segall. After listening to my father speak about the importance of the ‘right kind’ of packages, namely that the contents had to be designed around their usefulness on the black market, they offered him the job of organizing the new branch of “the Joint.” Mr. Segall headed the Branch and hired my father as the Deputy Manager.

Q: What work did your father do with JDC in Tehran and for how long?

A: Mr. Segall rented a basement in an office building complete with wooden crates as office furniture, where my father started working immediately. There, he worked 6 days a week until he left on November 1, 1945. During the time that he was the Deputy Manager, he hired and managed a staff of 30 individuals from 10 different countries, who spoke 8 languages and corresponded in around 6 languages. Through my father’s efforts, motivation, and training, he managed the ‘production’ of 10,000 packages per month! These burlap packages wrapped in string were reengineered under his direction. Assuming that the packages arrived at their destination of Siberia or Uzbekistan, materials were sold so that individuals could buy bread and food staples. Contents included things like vegetable oil, soap, shoes, shirts, underwear, and sugar, and were purchased in Iran, India, Palestine, and South Africa and from U.S. Lend-Lease supplies in the Middle East.

Crates set to be sent from Jerusalem to Tehran via Baghdad. They contained shoes to be distributed to the Polish Jews in Central Asia; Jerusalem, British Mandate Palestine, 1945. JDC Archives

Q: Why was this work so important? What did it mean for those involved?

A: The work was important because each package-assuming that it arrived at its destination- extended the life of the recipient by two to three months! My father instilled an ‘esprit de corps’ in the workforce, inspiring them to treat their work as an activity that would save lives as opposed to simply a job. As a result, they did not leave things for ‘tomorrow that could be finished today’, even though working in a basement with no air conditioning at relatively modest salaries was far from ideal! As a refugee, he would have taken any job he found, but this work was not just a job for him – it was a devotional experience. It was a mission for him to save lives.

Q: How old were you during the war and what are your most vivid memories from your time in Uzbekistan (USSR)?

A: I was 7 years old when the war began and 12 and a half when we came to the United States as refugees. I am blessed with a very good memory, so I remember daily life, including the separate times when each one of us was ill with malaria, typhoid, and typhus, among other things in between. I remember the times when I was able to just be a ‘kid’ and play, as well as the time when my brother and I were considered adults and our votes counted equally to our parents on major family decisions.

Tehran felt like the promised land. It was a wonderful experience to be there. I had the opportunity to learn several languages including Uzbek, Urdu, and Persian. I also took an active role participating in the street life of Tehran. I would rent bicycles and roam around the city, joining my parents on Saturday afternoons at a street café. It was a lovely time. I felt free. I even befriended a Czech family that lived above us and when they left, I inherited their dog. It was a very nice life there.

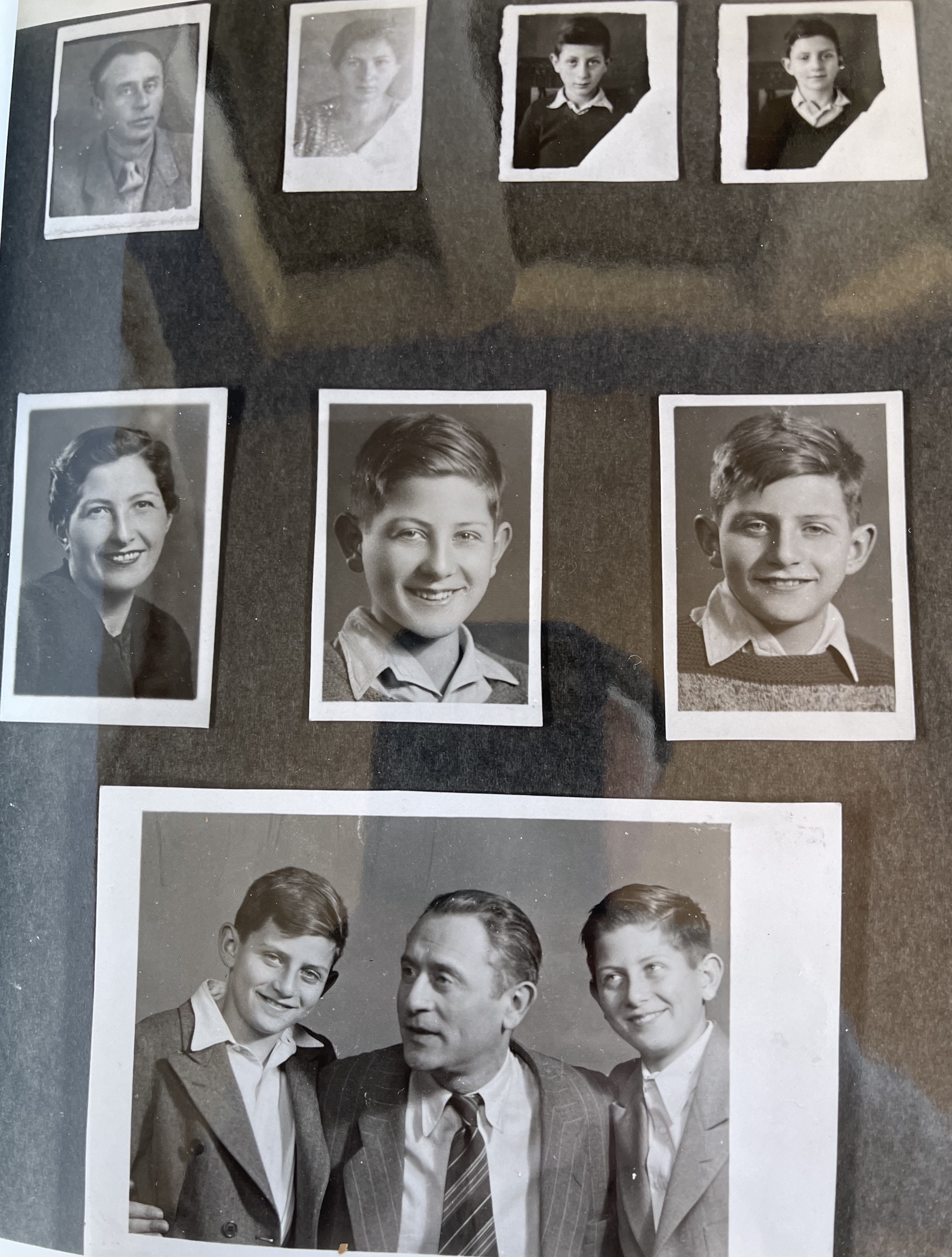

Page of the Landau Family album, c. 1942-1944.

Note the contrast of the photos at top, taken in Bukhara, Uzbekistan by a street photographer at the request of the Australian Consulate for an exit visa in December 1942, to the photos at bottom taken in Tehran 1943/44, after the family regained financial freedom thanks to the support of relatives in Australia and the US, and the paid position of Dr. Landau as Deputy Manager of JDC.

Q: When did your father leave Tehran and where did he go?

A: My father left Tehran for Australia on November 1st, 1945 on a month-long journey via Bombay, Karachi, Colombo (or Sri Lanka), Bangalore, Perth, and Melbourne, arriving in Sydney on November 28th. He stayed in Australia many months, during which time he gave several talks (pro bono) to various relief organizations about the importance of the activities of the Joint. He took it upon himself to speak publicly in major synagogues and other venues in Australia to hundreds of donors, which resulted in a rebirth of enthusiasm for the JDC with added donations.

Q: How did you reconnect with JDC?

A: I was never disconnected! Even though my father was not active in the organization on a professional basis, he respected its work from ‘way back’. While a student at the University of Vienna in the early 1900’s, my father was active in the Zionist Movement. He worked with JDC after World War I in Vienna, when many Jewish students needed help returning to their studies that were interrupted by World War I. When we settled in New York, JDC was an organization that my father supported. The company with which I worked overseas for over 10 years, five of which in Geneva, Switzerland, had a Foundation that enabled us to be very involved in Jewish activities and causes, including JDC and ORT. When I came back to the United States 50 years ago, I continued my support of JDC.

About the Author

George Landau is an entrepreneur and retired financial planner who lives in Tiburon, California. This interview was shared with his permission. The documentary Lies and Miracles: Childhood in a Siberian Camp chronicles his family’s story. For further information, please contact the JDC Archives for George’s contact information.