Researching His Roots in the Ukraine

Former JDC Country Director learns more of his family’s fate

The following is a story written by Zvi Feine, former JDC Country Director for Romania and Poland, who had a unique and meaningful roots experience in the Former Soviet Union as part of a JDC staff trip. This story was shared with his permission.

In the Feine family, the memory of the Holocaust was always meaningful. Even so, we did not feel that the Holocaust had touched our family personally. Our ancestors emigrated to the United States at the turn of the 20th century and, luckily, had not been directly harmed by WWII. Only later did we grasp that my father’s aunt Mia, her husband Shmuel Hirsch Gorin, and their three children—Shloime, Mindel, and Raizel—had been murdered, along with other, more distant relatives.

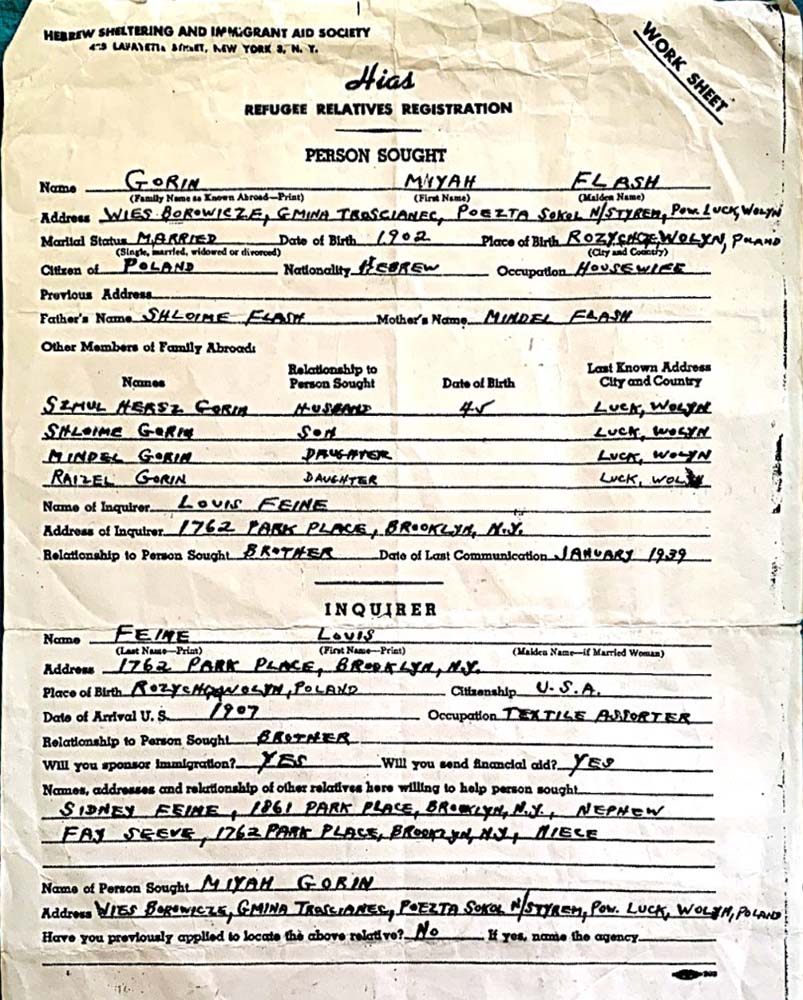

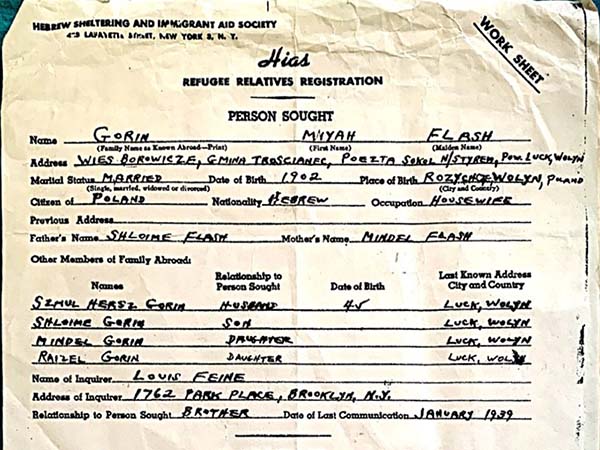

I remember the time I asked my father for information on those close relatives who had died. He gave me a form from HIAS (Hebrew Immigration Aid Society) that he had filled out in 1940—a request to contact, and transfer funds to, the family in Ukraine. This form turned out to be crucial in discovering the story of that same branch of the family that had perished in the Holocaust.

I served as JDC Country Director for Poland and for Romania. Once the border with Ukraine opened in 1992, I suggested to my father that I try to find out what had happened to the family. My father was adamantly opposed to the idea. He said that almost all the Jews in the area had been killed in the war. It was a very painful subject for him, and he said that my going there would reopen old wounds. He asked me to give up on the idea, and I honored his request.

But the subject gave me no peace.

In 2004, JDC sent a group of senior staff to the Former Soviet Union to study the Holocaust, in order to deepen our knowledge of the remaining communities and the Holocaust survivors who were being assisted by JDC. Whoever had family roots in Ukraine connected to the Holocaust would get a free trip there, including a thorough investigation into what had befallen their family. I approached my father again. I explained to him that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. In the end, he relented and gave his consent.

According to the family story, Shloime and Mindel were given tickets to travel by boat from Odessa to New York. The couple reached Odessa, saw what a high price had been paid for the tickets, and decided to sell them and buy an inn and restaurant in Borovichi, where they would not be far from other relatives in the area. They believed that, instead of setting off for an unknown country, they would be better off making a reasonable living by purchasing an inn. By doing this, in effect, they sealed the fate of this branch of the family.

The family in the USA were disappointed. They kept up correspondence with them and occasionally sent money. The last letter from them was sent in early 1939.

From then on, all attempts by the family in the USA to get in touch with them were unsuccessful. The document that my father filled out remains as a silent testimony to the efforts of the family to locate the family through HIAS.

The JDC senior staff member responsible for Ukraine, Itzik Averbuch, asked me for all the documentation and information about the family that we had. Apart from the HIAS form and a few names, I had nothing to give him. Itzik looked at the form and understood immediately that it included an address in Ukraine. He took me to the office of his colleague, Dr. Aharon Weiss. Dr. Weiss went over to a map of Ukraine that was hanging on the wall and grasped straight away that we were talking about the area of Lutsk and the River Styr. He searched along the river until he found the village of Borovichi. This was a breakthrough for me.

Itzik sent the form to JDC-Lvov and a local historian by the name of Nakonechny took it upon himself to research the family’s fate and accompany the group on my visit there.

In October 2004, my Romanian driver took me to the border with Ukraine, where I was met by a driver from the local JDC office who took me to Lvov. In Lvov, we participated in seminars, tours, and sightseeing, and divided up into groups that went into the field on the roots exercise. On October 18, 2004, we set out from Lvov for Lutsk and from there to Rozhishche, Borovichi, Chetvernya and back to Lvov. My relatives used to live in this area, which then contained large Jewish communities. Today, there are only a few Jews left in Lutsk and central towns in the region.

In Lutsk, the director of the JDC Hesed (a network of centers, set up by the Joint throughout the FSU, that supplies health and welfare services to needy Jews) briefed us on events in the area during the Holocaust, the current community, and services provided to local Jews by the Hesed. From Lutsk, we set out for Rozhishche, where most of my father’s relatives and my maternal grandparents’ family lived in the 19th century and at the start of the 20th century. Today, not even a single Jew remains there. The regional Jewish cemetery had been fenced off, so we could not enter. I said a prayer in memory of my relatives.

The highlight of the visit was Borovichi, in the Volyn region. Only five Jewish families were living then in the village, including our family, the Gorins. In 1941, they were all deported to the Kolki Ghetto. Liquidation of the ghetto began in September 1942. With the help of volunteers from the Ukrainian police, the Germans surrounded the ghetto and murdered the Jews in pits outside the village. A few managed to escape, but they were caught and shot.

Some 62 years had passed, and here was I, a family member, arriving in Borovichi in a minibus, together with colleagues from JDC, on a roots trip. I felt great excitement together with uncertainty as to what awaited me.

On the outskirts of Borovichi, a man was waiting for us, driving a horse-drawn wagon. I got the impression that he was disappointed by my arrival, but I did not yet understand the reason. He asked me about myself, the family, and my connection to the Gorin family. He told me that, as a child, he had known the children from the family and that he and his sister had studied together with them at the village school. He added that there were some people waiting to meet me at the town hall—the mayor, as well as a few women who had been friends of the family and had studied together with the children from the family. They would tell me about the family and all they knew about what had happened in those days.

But before we went there, he said he wanted to give me a gift and presented me with an item that had belonged to the Gorin family—a knife that had been used by Shmuel Hirsch Gorin, owner of the inn-restaurant. He had used this knife to slice kosher salami for his customers. On the knife was a kashrut sign, indicating to him that it was for meat. I was very moved. This original knife is the only item that belonged to our family and survived the Holocaust.

Shmuel Gorin’s knife presented to Zvi Feine.

I said goodbye to the wagon driver when we reached the office of the mayor. A group of seven or eight elderly women who had known the Gorin family were present. The elderly women gathered around me and were very interested to learn who I was and how I was related. Again, I had the impression that they were a bit disappointed to see me. I asked the interpreter to ask them and, indeed, they confirmed this was true. It turned out that a rumor had spread that Raizel Gorin was returning. They had all hoped to see her but, instead of the lost Raizel, only a relative had arrived.

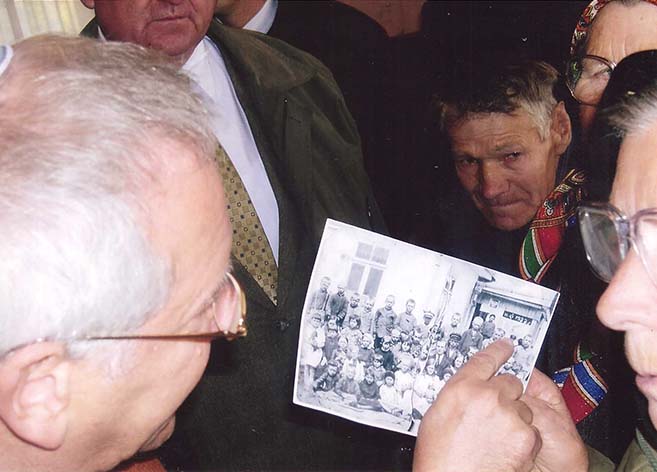

The women showed me a class photo from their school, in which you could see the children of the Gorin family. They pointed out Raizel and talked about Mia and Shmuel Gorin who, before the war, would travel every week to Rozhishche to visit their relatives and to buy kosher produce for the inn-restaurant. They told me about Raizel and how special she was.

Women of Borovichi showing Zvi a photograph of their class at primary school, in which you can see the children from the Gorin family.

The women took me to see the plot of land where the Gorin family home and the inn had once stood. They told me how they had lived together with the Jews, about the good and friendly relationship they had had with the Gorin family, who were loved and accepted in the village, and with the other Jews.

In 1941, when the family were sent to the ghetto, together with the rest of the Jews from the village, Raizel, the youngest daughter, was about 12 or 13 years old. That same year, because of the extreme hunger in the ghetto, Raizel escaped from the ghetto and found her way, three times, to Borovichi—almost 20 kilometers away from the ghetto. She would stay there for one day, or a bit more, and try to collect food from neighbors and friends to bring to the family. The women told me that they did not have much to give her, since the people in the village were starving as well, but even so, they would give her a few items of food. They all stressed that they had loved the Gorin family and Raizel, and that they had wanted, with all their hearts, to help them.

Once when Raizel came, she brought them the meat knife—a gift from her father, Shmuel—to thank them for the help they had given the family and for the food they had sent back with Raizel.

The fourth and last time Raizel came to the village, she was very upset and could not stop crying. She told them that, one night toward the end of August 1942, all the Jews of the ghetto had been taken to a killing area and that the Germans had murdered everyone, including her parents, brother, and sister. She told them that, from her hiding place, she saw with her own eyes how all the members of her family were killed. By some miracle, she had hidden and managed to escape to Borovichi.

“What happened to her after that?”, I asked the women. They told me that the wagon driver’s family hid her for two weeks until she had pulled herself together a bit. “And after that?” I wanted to know, and the women told me that after two weeks they had been afraid to continue hiding her, because there were informants in the village. They thought it would be safer for her to move to the neighboring village of Chetvernya which had a small ghetto, in order to find shelter and join other Jewish families.

And so, they took her to the River Styr, pointed her in the direction of Chetvernya, and told her to go through the fields until she reached the ghetto. According to them, they saw Raizel walking toward the field in the direction of the village but, from that point on, never heard from her again. I thanked them very much and promised to find a way to express my gratitude to them for helping the Gorin family.

After a farewell ceremony, we drove to the nearby Chetvernya Ghetto. The historian told us that 200 Jews had lived there and that they all had been wiped out by the Germans.

Was it still possible that Raizel had survived? Again, I asked for Itzik’s help. According to him, the chances that she had survived were close to zero. Itzik enlisted Danny Gechtman, JDC Regional Director for Ukraine, who sent Gersh Fraerman, Director of the Rovno Hesed, together with Nakonechny, back to Borovichi, Chetvernya, and the villages in the area. They went from village to village. They interviewed villagers in Borovichi and asked what happened to Raizel but found nothing. Danny wrote me: “Raizel’s fate is unclear. The most likely scenario is that she was killed, together with the other 200 Jews, who were then buried in a mass grave in Chetvernya. We did our best to find out what happened to Raizel.” I had no choice but to accept my colleague’s conclusions as to what had befallen Raizel, age 13 at the time of her death.

May the memory of the Gorin family, and the other Jews who perished there, be for a blessing! We will not forget the heroine of the story—Raizel, who was so vibrant and daring.

Explore your own family history in the JDC Archives Names Index.